A New Year’s Eve Toast to Thomas Jefferson and James Hemings

- Deborah Llewellyn

- Dec 31, 2021

- 11 min read

On New Year's Eve, I thank Jefferson for my glass of bubbly. Jefferson is known as a founding father, but he was foremost a foodie. If you have visited Monticello, you saw the vast gardens and learned about horticulture experiments that he documented with devotion. He was always a farmer at heart, but it was living in France, 1784-1789, that changed what he ate, and what you eat. Champagne was one of many foods and beverages that Jefferson made popular in America upon his return.

My neighbor, Elizabeth Bulla Cooper (Bet), is a culinary sage who enlightened me on the subject of Jefferson's cuisine by giving me a copy of the book, Thomas Jefferson's Crème Brulee, written by Thomas Craughwell (2012). Bet has refined elegance, a person who gardens in cashmere. Now in her 90's, she lives alone but still eats well, cooking French delicacies for one or a few lucky guests from her well-fitted kitchen. I tend to prepare big plates of Southern favorites. From Bet, I've learned how Jefferson ate.

Bet gave me the Craughwell book as a gift with the following note: "For Deborah, who well understands the power of the dinner table." I was flattered. She inspired me to branch out, and serve lighter meals with a focus on the flavor in each small bite, and of course wine selected for each course.

From Bet, I was better able to appreciate that a single stuffed grape tomato has exquisite taste when served as a stand-alone, in the method of Chris Salans, an award winning French Laundry Restaurant chef, who now reigns at Mozaic Restaurant in Bali.

I had my nudge to French cooking in 1978 but was too unsophisticated to appreciate the wedding gift cookbook from Glen Kaufman, "The Art of French Cooking." It was written in English but read like a foreign language to me. I gave the cookbook away, focusing on refining old southern recipes.

It took a while but I've come to understand how French techniques transform American southern cuisine.

To make beef stew, I now slow braise beef with herbs and wine or ale, then layer with carrots, potatoes and fresh thyme until fork tender, and finally top the cast iron delicacy with buttered onion slices browned to a caramel glaze It took a while but I've come to understand how French techniques transform American southern cuisine.

With the foolish toss of that grand cookbook, I've come to appreciate the wisdom of my Aunt Mergie who told me this: "Never throw anything away, just build an extra room on your house. Everything comes back in style, or your appreciation for it grows over time."

Throughout his life, Jefferson had a fascination with food. Historical archives contain over 150 Southern recipes and adaptations penned by Jefferson. Southern cuisine was meat-prominent, but Jefferson believed that meat should be eaten as a compliment to vegetables. He designed extensive gardens at Monticello and traded seeds and fruit trees with other horticulturists.

Author Thomas Craughwell wrote that "Jefferson was considered one of the most cerebral of American presidents." He was a "political philosopher, an amateur naturalist, an inventor, a zealous bibliophile, an inventive tinkerer, and an ardent gardener." The Library of Congress was formed from his library of over 6,000 books.

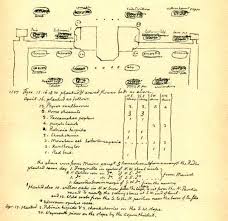

Jefferson kept a Garden and Farm Book for 53 years recording myriad details of crops and plantation life. Jefferson once wrote "there is not a shoot of grass that springs uninteresting to me." According to Craughwell, the scientist in Jefferson, " recorded which varieties he acquired, the characteristics of each plant, the manner in which they were planted, how they thrived, and the date they were harvested and served to him at dinner."

With the help of over 200 enslaved servants, he experimented with ninety-nine species of vegetables and three hundred varieties. He cultivated plants unknown to his neighbors that included tomatoes, peppers, eggplant and peanuts. The gardens were also designed for visual aesthetics, had a resting pavilion in the center, and a ten feet high fence around his garden to protect it from wildlife. He had an orchard of 400 fruit trees, a vineyard and berry garden. His inability to produce fine wine frustrated him.

In 1784, our newly formed government sent Jefferson to Paris for five years to negotiate treaties of commerce with European powers. Jefferson went to France with an aptitude for food and fine dining that would be exquisitely refined over five years. He packed with two ambitions, not just to achieve the assignment, but to also learn about the celebrated French cuisine.

Jefferson struck a deal with his trusted and talented enslaved servant, James Hemings, to accompany him to Paris to learn the art of French cooking. They agreed that James would be granted opportunity to study with the most famous French chefs and upon return to Monticello would be granted his freedom once he taught a replacement chef how to prepare French cuisine.

From this story, we learn that Jefferson was not always a man of his word. James Hemings became our first American French chef, learning the language and subtleties of fine food and wine, so much so that Jefferson was reluctant to fulfill his side of the bargain. Jefferson postponed his agreement to grant freedom to James for over four years upon their return. From my reading the facts of James's life after slavery, I surmise that Jefferson may have held a childish grudge toward James because James accepted his freedom and "abandoned" Jefferson.

Jefferson's views on slavery were inconsistent. While he condemned the institution as an abominable crime, he relied on enslaved labor all his life and did not emancipate his slaves in his will as planned due to his great debt. He had a conflicted relationship with his enslaved workers, especially those in the Hemings' family.

Jefferson's wife Martha Whayles had six half-siblings from her father's concubine Elizabeth Hemings, an enslaved African American. When Whayles died in 1774, he willed his 132 slaves to Jefferson and daughter Martha, including Elizabeth Hemings and the six children that Whayles fathered. Jefferson doted on this talented and skilled group of Hemmings siblings, and depended on them to help realize dozens of inventions and ideas bubbling in his head like the champagne. But that's another story you can read in the Pulitzer prize winning book, "The Hemingses of Monticello," by Annette Gordon-Reed.

The Hemings children included James who traveled with Jefferson to learn French cuisine and his young sister, Sally, who took care of Jefferson's children, Patsy and Polly, in France. Jefferson needed a companion for his mother-less daughters; Jefferson's wife, Martha, had died while giving birth to Polly.

Theoretically, upon arrival in France, the Hemings' siblings could have declared their freedom under the French law. Jefferson was aware that he walked a thin line between having them and losing them. He paid James and Sally high wages, purchased elegant clothing for them, and gave them personal freedom to enjoy Paris. Both James and Sally acquired fluent French, whereas Jefferson learned to read French but never spoke it well. Interestingly, James was expected to pay for his cooking classes from his salary. Sally accompanied the girls to social events and made many friends in Paris, who she corresponded with for years.

During the French years, Jefferson and Sally Hemings developed a close and trusting companionship, while Jefferson simultaneously enjoyed a romantic attachment with Maria Costway, an English artist and author, who was married to an unfaithful husband. When Sally Hemmings returned to Virginia with Jefferson, she was pregnant. Over the years Sally remained by Jefferson's side at Monticello and bore him six children that he loved and pampered, but who remained enslaved property.

After Jefferson's death, his daughter Martha (Patsy), gave Sally her freedom. Four of Hemmings and Jefferson's children lived to adulthood, and from this family arose many scholars, intellects and chefs over the next two hundred years.

While in France, James Hemings prepared meals at the highest French standards to some of the most discriminating men and women of France at Jefferson's elaborate dinner parties. There is historical documentation of a few of the recipes James mastered and brought back to Virginia. Eight recipes written in his own hand still survive today. These are important archives from America's first French chef. Over 150 other French recipes were written in Jefferson's hand and passed down to his daughters and granddaughters.

Some of these recipes have become American classics: fried potatoes which Jefferson knew as pommes frites (now we know why Americans call them French fries), crème brulee, and macaroni with cheese. These were the humbler dishes Hemings had mastered, and they would become the easiest recipes he would teach to his apprentice at Monticello. But James also learned complicated French recipes and techniques of layering stocks and sauces for flavor and then artfully presenting small portions of food for each course, each with a compatible wine.

In France, Jefferson acquired a passion for pasta and drew out the design for a pasta press that he planned to reproduce back in the United states. He frequently served mac and cheese at dinner parties. The Craughton book includes Jefferson's recipe for making macaroni, as well as his illustration of the pasta machine.

The Jefferson's and Hemingses spent a magical five years in France. In 1789, George Washington asked Jefferson to join his cabinet. Jefferson came down with a violent migraine headache that kept him in his bed for six days. While Jefferson suffered migraines throughout his life, he had none in France until his departure. Surrounded by intellects, artists, scholars, scientists and grand cuisine, he enjoyed one of the richest personal periods in his life. Sally and James likely shared Jefferson's sentiments; in France, they lived cultured lives without the scourge of racism.

The Craughton book tells us that "the menu at Jefferson's final dinner party in Paris is unknown. We do know how it was served. Jefferson adopted the French method. Between each two guests was a small table where servants placed platters and bowls. The servants then left the dining room and the guests helped themselves and enjoyed free and open conversation unstifled by presence of servants." He continued this practice at Monticello.

Before departure, Jefferson filled eighty-six crates with kitchen utensils, cooking equipment, including an Italian pasta machine, and specialty foods such wines, parmesan cheese, olive oil, anchovies and his favorite mustards. Waiting for calm waters at the Port of Le Havre, Jefferson purchased two sheep dogs and a German shepherd that delivered two puppies before they sailed. (This point added for my readers who are dog lovers.)

Back in the United States, Jefferson assumed duties to flesh out the structure and laws guiding American government. He was immediately faced with heated arguments between Hamilton and Madison over divisions of federal and state powers. So he decided to hold a private dinner party to soothe anger and inspire compromise.

Drawing from his past five years, Jefferson and James Hemings served a six course French dinner with a different wine at each course to Madison and Hamilton. Dessert was vanilla ice cream, another French dessert made popular in America by Jefferson. The ice cream was served with champagne, macaroons and meringues. This is considered one of the most momentous private dinners in American History and it was prepared by James Hemmings.

Jefferson postponed James's freedom because he needed him as his personal chef when he took on federal government duties in Philadelphia. The concept of freeing him and then hiring him apparently did not occur to Jefferson. Two years later, when they returned to Monticello, Hemings was still enslaved. Jefferson selected James's younger brother, Peter, as James's apprentice. The tutorage took two years.

The kitchen equipment from France was now installed, and Jefferson constructed a brick oven, popular in France, that replaced the necessity of cooking over open fire. Elaborate methods were devised to keep food hot while moving it from the kitchen to Jefferson's office where more servants transferred the cooked food to porcelain and silver serving dishes. These were placed inside a revolving cabinet and when turned the food appeared in the dining room. The plates were placed on small tables between each guest and the servants left. It appeared to the guests as if by magic, but required an army of enslaved servants.

Craughton's book ends with two chapters on Jefferson's love affair with wines and fine food, especially vegetables. In 1819, looking back on his life, Jefferson wrote, "I have lived temperately, eating little animal food, and that not as an aliment, so much as a condiment with vegetables constituting my principal diet."

Regarding vegetables, he was one of the first Virginians to grow and eat tomatoes when most Americans thought the tomato was poisonous. He raised eighteen varieties of cabbage. He grew hot peppers for sauces, and tended his asparagus patch with great care. His garden book includes entries over twenty-two years recording the date that the first plate of asparagus was served each spring.

Jefferson grew vegetables from Africa brought by enslaved people including okra, black eye peas, peanuts and watermelon, and honed recipes like hoppin' john, okra soup, and gumbo. Fried chicken, another African food, was served with cornmeal mush (polenta or grits) and cream gravy. He also grew millet and sorghum. He grew sesame seeds, toasted, and tossed in salads or pressed for sesame oil. Jefferson adored lettuce, adopting the French tradition of serving salad as a dinner course.

Jefferson once described wine as "necessary for life." In the years before France, he tried to produce wine with little success. He became partners with Mazzei, a French wine maker who identified 400 acres on Jefferson's estate that Mazzei thought might be suitable for growing grapes to produce burgundy. While the two had little success with the grape crop, they became fast friends, with Mazzei taking up America's struggle for independence. After Jefferson completed a rough draft of the Declaration of Independence, he showed it first to his French/American friend, Mazzei, for his opinion.

In France, Jefferson served the following wines: Chateau d'Yquem, Chateaux Margaux, Latour, Lafite, and Haut-Brion. He shipped cases of these wines from France to serve during his Presidency and to guests at Monticello. He gave guests their first opportunity to taste champagne and in doing so made this the favored wine for festive occasions in America.

According to Craughton, Jefferson enjoyed fine wine the way he enjoyed fine food, giving him pleasure, something he could share with guests, and something he could study. For a wine lover, he drank abstemiously, never more than three or four glasses at dinner. Wine glasses at that time were 1/3 the size of ones currently used.

Jefferson continued to purchase favorite wines and foods from France. "Sometimes a shipment of five hundred bottles would arrive in a single day. Wine was something he could not live without. Even in his final years, when he was deeply in debt, he continued to purchase wine from France. At his death, there were 600 bottles of French wine in the Monticello cellar.

Our story of Jefferson's love affair with French food takes us back to James Hemings, the only person in America who shared Jefferson's passion for French cuisine. For this reason, Jefferson was reluctant to grant James his freedom. In 1796, after two years of intense training, Peter was ready to take over the kitchen and James was finally granted his freedom.

When Jefferson became president he sent word to James, who was working in a tavern in Baltimore, that he would like for James to serve as his chef. James told the messenger that he would like to hear some words about the position in Jefferson's own hand. Jefferson did not respond to James's request, which could be considered a plea that Jefferson show respect to James by contacting James personally, offering the position and explaining the terms.

Instead, he hired a French chef for the President's house and then brought two young enslaved women from Monticello, Edith Fosset, age 15, and Fanny Hern, age 18, to study under the French chef. Once adequately skilled, the French chef returned to France, and these two enslaved women took over meal planning and preparations, becoming America's first female French chefs.

From his years in France, Jefferson learned that fine wine combined with lively conversation can serve a political purpose. Dinner parties at Monticello were so popular that the house was constantly full of guests who stayed sometimes for extended periods. Jefferson found that serving the best food and wine around can get you into a great deal of debt.

Jefferson was a complicated man who wanted the best of everything, He loved our native foods adapted from Indians and Africans. But he also "traveled with eyes wide open and taste buds that were eager for new delicacies. Jefferson never abandoned his native cuisine; he married it with those of France."

In 1801 James Hemings returned to Monticello to visit his family and friends while Jefferson was away on vacation. When Jefferson returned to Monticello, James left and went back to Baltimore. A month later James killed himself, a sad ending, that leaves many questions. I take solace to remember that James Hemings's legacy lives on. Together, Thomas Jefferson and James Hemings founded a culinary dynasty in America this New Year's eve raise a glass to Thomas and James.

Photo credits

Photos of Monticello from Monticello website

Photo of Sally Hemings from imdb.com

Photo of James Heming from UnCutFun

Photos of Hemings descendants from BBC, Houston Chronicle and NBC archives

Comments