My venturesome husband and children taught me this: I have to leave my comfort zone and expect a few hardships in order to experience the natural, cultural and architectural gems that exist along the road less traveled. This is the life my family breathes, and thankfully, they patiently drag me along.

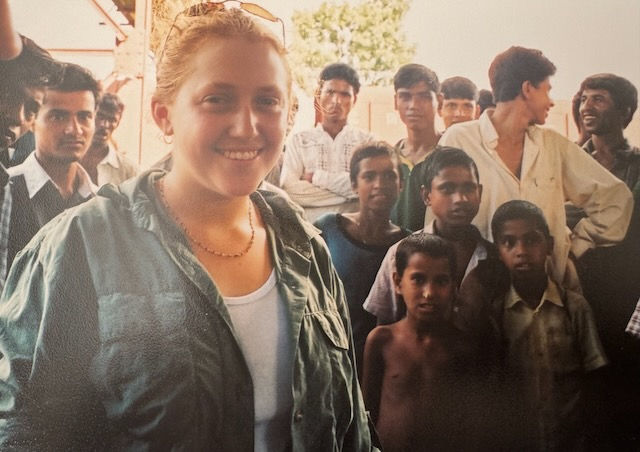

During the years we lived in Bangladesh from 2000-2005, I traveled the country to learn and support indigenous parenting and early childhood education. My work took me to places where one doesn’t find a cup of coffee or western toilets, while mosquitos that carry malaria and dengue are in abundance as well as beautiful children and warm-hearted families, making the best they can with what they have. I learned a lot from these villagers who manage daily hardships with hard work, ingenuity and dignity. That said, I eagerly returned home to Dhaka, grateful for my cushy life.

Over five years in Bangladesh we took only two family vacations outside Dhaka to explore other regions of the country because travel and accommodations were challenging in a country without a tourism industry.

On one of these vacations, we booked a clunkish boat that belched clouds of diesel to look for tigers in the mangrove forested islands in the Sunderbans National Park off the coast of Bangladesh.

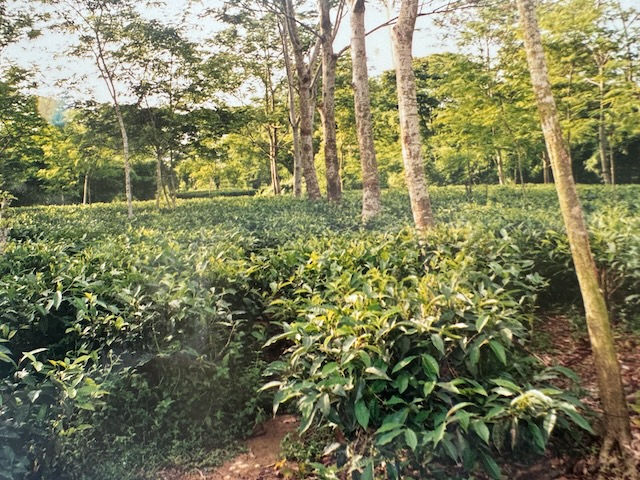

Another time we took a train to Sylhet and lodged in a tea-growing estate. The train station memory that stands out is being encircled by young adult men unabashedly staring at us, particularly our red-haired daughter.

Twenty years later, our daughter, Bronwyn, who is now posted to Bangladesh for environmental work told me that the biggest change she’s noticed is that Bangladeshis no longer stare at foreigners. They’re far more absorbed in watching YouTube videos on their cell phones.

Our son, Chas, who spent his formative years (ages 13-18) in Bangladesh longed to travel over the entire country. Chas’s closest friends were Bangladeshi, along with still-girlfriend, Katerina, who has spent most of her life in Bangladesh. He grew to love everything about Bangladesh.

As a teen, he took buses to the end of the line and walked along the rivers and paths through the rice fields, strumming his guitar. He developed a strong interest in the Baul culture, an order of religious singers known for their unconventional behavior and for the freedom and spontaneity of their mystical verse (Wikipedia). Chas took trains in search of “Baul Melas”, where Bauls gathered by the thousands to chant and sing long poems that revealed their life philosophy, which is said to have influenced the American Transcendentalist’s movement (Emerson and Thoreau). As a high school teen, Chas developed personal friendships with some of the great Bauls of the time such as Kartik Das Baul.

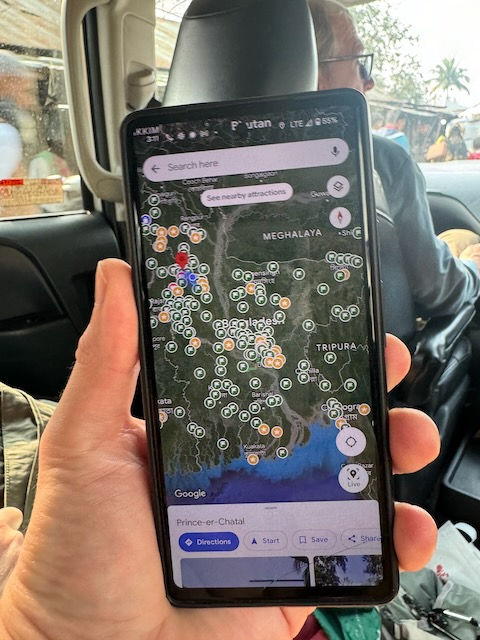

Over the past three years, Chas has returned to Bangladesh for several months at a time to visit Katerina. While there, they travel to remote areas to explore archeological sites that Chas and Katerina longed to see since their youth. Chas has a map of Bangladesh on his phone pinned with all the sites he wants to see and when he visits one he changes the color of the pin. When he returned to the U.S., he told me how fascinated he was by Bangladesh’s ancient history. He believed that I would also love to see these archeological sites.

He told me this: “Traveling is not so difficult these days, Mom. You should go and see what great cultures existed two thousand years ago. Well,” he added, “they’re mostly in rubble but you’ll get the idea.” There’s a lot to see. There are at least 2,500 archeological sites in Bangladesh, whereas only 354 sites have been partially excavated and/or protected under the provisions of the Antiquities Act. The majority are in obscure locations and challenging to find without a Google Map.

This year, Chas made plans to return to Bangladesh in January and February. Charles and I decided it would be a great time to return to Bangladesh. We wanted to check out Bronwyn’s life in Dhaka and the timing was perfect to also spend time with Chas and Katerina. Once children grow up and leave home, these times with everyone together, sharing conversations and experiences, are precious.

Photos Below:

Author and husband standing with Bashar who took care of our family during the five years we lived in Dhaka and now takes care of Bronwyn. Bashar is an exceptionally talented man, gentle and kind with a great sense of humor, who can make anything happen. Just what our whacky creative family needed. We have stayed in close contact with Bashar over the years. Years ago he assigned his whole village to build us a teak river party boat. He carved vegetables into animals to delight our kids and visitors. He also built a rooftop pergola and garden for Katerina. If he can't handle the task he knows someone in old dhaka who can. Seeing him was one of the highlights of our trip.

Bronwyn in Bangladesh work clothes - a sari- standing in her beautiful living room.

Here we are having lunch with dearest of friends - Faiyaz (chas's childhood best friend) and his sisters Farah and Fiona. Katerina's best friend Istella is on back left across from her dad who is a boat captain on large vessels and entertained us with squashbuckling tales from the high seas. Istella is a graphic designer with immense talent and notoriety in Dhaka. On the right we have Katerina, Faiyaz, Fiona, and Chas. Holey restaurant, a popular bakery and cafe among foreigners made the news in 2016 when it was raided by terrorists who shot and killed 22 diners, mostly foreigners. This led to Foreign Embassy closings throughout Dhaka for several years. All terrorists were arrested and prosecuted. Holey, once again is a delightful gathering place for friends in its new more secure location. Bangladesh is calm and welcoming.

Back to the story:

Our visit to Bangladesh would include a 4-day adventure led by Chas and Katerina to explore the ancient world of North Bengal where over 1,000 archeological sites have been identified in the fertile Ganges River delta.

Exploring North Bengal with our kids would provide a deep dive for Charles and me into the complicated history of the small kingdoms and empires that once dominated the region. Chas and Katerina worked diligently on trip planning to share the significance of Bengal’s ancient history to the rest of the world.

Chas identified the most fascinating sites, and Katerina worked her contacts to find comfortable guest houses that assured us they would provide new, not ripped, torn or holey mosquito nets and a pitcher of boiled drinking water in our rooms.

She rented a clean, well-functioning van with a cheerful driver willing to go off-road. Bronwyn planned enjoyable entertainment to close each day – games and a bottle of bourbon. Bangladesh is a dry country, but thankfully, one of the Llewellyn’s still has American Embassy commissary privileges.

Charles added greatly to the trip by down-loading the Apple pod cast, Empire, that our friend Stephen Pappas recommended as trip preparation, especially the episodes discussing the early history of the East India Company in India and Bengal. Bronwyn brought along a wireless speaker for a quality listening and discussion as we drove from one site to site.

Historians William Dalrymple (British citizen living in India) and Anita Anand (Indian born, living in UK) narrate the Empire Podcast. They explore the stories, personalities and events of empires over the course of history. How do empires rise? Why do they fall? And how have they shaped the world around us today? [https://podcasts.apple.com/gb/podcast/empire/id1639561921]

Chas’s trip plan included numerous ancient sites in northwestern Bangladesh that border big rivers –Brahmaputra on the west and Ganges in the South. Besides the ancient sites, we would see several of the old palaces (Rajbaris) built in the 1700 to 1800’s by local governors and smaller kings called Zamindars.

Bronwyn reminded us that the majority of the country lies in the delta of these two great rivers that flow into Bangladesh from India. “Each year, 60-70% of the country floods. The soil is intensely rich and productive, allowing them to grow three rice crops per year without irrigation or fertilizer. This provides the reason for such a long, rich history of civilization in this region. Because all the buildings were made of bricks, the ruins of ancient cities and temples are less visible that Angkor Wat in Cambodia or the Mayan pyramids in Mexico that were built with stone,” she explained before the start of our trip.

The trip got off to a bad start, but that’s how these excursions with my family seem to go.

For the trip I packed clothing that could take some grunge and shoes for climbing over ruins, my down travel pillow, and packets of Starbucks coffee. I put my duffle bag on the floor in the guest bedroom. I laid a Ziploc bag with twenty-seven Starbucks coffee packets and creamers, as well as a pill box holding two prescription drugs, secured by a rubber band, on top of my bag. Then, we dashed off to dinner at Katerina’s apartment, which is a couple blocks from Bronwyn’s building.

After dinner, we returned to Bronwyn’s apartment and immediately spotted the remains of the foil packets and creamers scattered across the dining room floor. The pill box was missing. Did the dogs eat the pills, as well as the coffee and cream? I take these pills but can live without them, so losing them was not so critical for me. However, I was worried that the dogs would be harmed by the medications and the caffeine. I checked each coffee packet and discovered it was the cream that the corgis, Shwari and Corgi, were after. They had chewed on a couple foil coffee packets but abandoned them, not coffee drinkers. We never found the meds, so watched the dogs carefully overnight.

The next morning, we rose before daylight to go to the airport. Chas and Katerina planned to travel by uber and meet us at the airport. On the way we discovered that Chas and Katerina did not have an airline ticket. I had told the kids that I would pay for our airline tickets but Bronwyn thought that Chas had already purchased their tickets and so only acquired tickets for herself, Charles and me from her travel agent. At the airport, Bronwyn checked with the airline official outside the terminal while Charles and I waited in a cloud of mosquitoes that terrify me due to a previous bout of hemorrhagic dengue fever in 2004. The airline’s agent told Bronwyn that the morning flight was sold out but that her brother could get two seats on the afternoon flight.

Bronwyn was talking with Chas by phone, while simultaneously talking to the airline agent. After we got inside the terminal and checked our bags, Bronwyn discovered that she did not have her phone. Losing a phone is nightmare enough but in addition, her pass for the priority lounge was on that phone and unable to enter the lounge, we had to wait with the mosquitos. Stressed, she took out her IPad to track her phone and all she gathered was that the phone was in the airport, which was obvious. But who had it?

When we boarded the plane, her app, Find My Phone, showed that the phone was on the plane. She was relieved, realizing that she had dropped it in the bag that was checked and now in cargo. Things were looking up. Meanwhile, Katerina was on the phone with her contacts in Rajshahi, working out a day of activities for us to enjoy, before she and Chas arrived in late afternoon.

The driver, Mahzed Bhai, spoke little English but had a nice smile and knew our names. He was waiting for us outside the airport in Rajshahi and took us to the guest house at the BRAC Training Center. Katerina had arranged for BRAC to serve us a late breakfast.

BRAC, a non-governmental development agency, has transformed Bangladesh over fifty years. It has been an essential driver in changing the economic forecast of Bangladesh’s rural areas, creating opportunities for people living with inequality and poverty to reach their potential. [https://www.brac.net/].

BRAC is responsible for educating most of the young girls in rural areas and spurring women’s empowerment through enterprise development in rural villages. For example of BRAC”s Development approach, I think back to 2000. Major donors decided they wanted to provide a daily carton of UHV milk for undernourished children in the country. BRAC responded to the opportunity by launching a cattle and milking industry in a rural area, a village veterinarian training program to develop women’s skills to take care of the cows, a factory to process the long-life sterilization and to make the cartons, as well as a distribution center. Like most of BRAC projects, it resulted in hard cash employment and increased nutrition and standard of living.

We were shown to our rooms in the Rajshahi BRAC Training Center, which had been heavily sprayed with insecticide. We spread out the clean, but damp towels, and then went to the dining room to eat our breakfast of curried cauliflower and chapattis. From Dhaka, Katerina was on the phone with our driver, Mahzed, directing him to take us to meet up with Mariyam, an archeology student.

Mariyam knew Katerina from their experience flagging down a train when they were in an isolated rural area wondering how they were going to get from point A to point B. Mariyam laughed when she told us, “To this day, Katerina and I can hardly believe that a train actually stopped on the tracks and invited us to hop aboard.”

We were delighted with the city of Rajshahi, the starting place for our journey. The air was fresh and the rickshaws and trucks were dressed up in colorful paintings of flora, fauna and daily life. The streets were wide and clean.

We met Mariyam at a park on the mighty Parma River and took a walk along the concrete jetty that protects the shore line during the rainy season and provides a sturdy path for walkers. At this time of year, the river was barely a stream because it was the end of the dry season. The river has also been diminished due to a dam that India constructed upstream, taking essential river water from Bangladesh. Mariyam told us that her favorite pastime after university classes is to ride her bike from town to sit on a park bench and watch the sunset over the water.

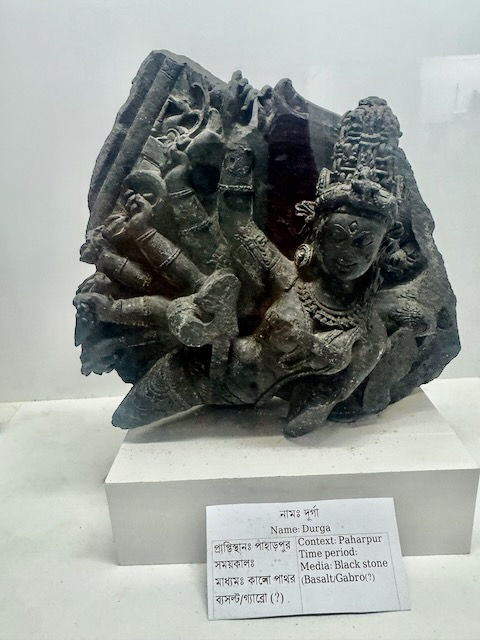

Next stop, Mariyam led us on a tour of the Vajendra Research Museum founded in 1910 by Lord Carmichael who was an agent for the East India Company and developed a passion for archeology in the region during his post, as we would learn along the trip and from the Empires Podcast. The museum has three rooms of stunning black stone carved statues that are a thousand years old, remarkable for both the exquisite carvings but also because these stones did not exist in Bengal and had to be brought in from India. Many of the statues featured the Hindu God Vishnu, probably due to his control over the weather, so important to this rich agricultural area.

We said goodbye to Mariyam and went to tour the Sopura Silk Factory. Katerina had organized this activity especially for Charles who has keen interest in weaving techniques. The weaving room was deafening. We stepped just inside the door only long enough to see all the people laboring over the machines wearing no ear protection, and then dashed back outside to see other (quieter) phases of the silk production process.

We were delighted to receive notice that Katerina and Chas had arrived so we went back to BRAC to meet up with them and enjoy some more curried cauliflower along with fish, carrots, rice and lentils for dinner. It was the end of winter when cauliflower is plentiful and spring veggies are just sprouting.

We took off the next morning with Chas in charge. All the mystery and excitement he had promised was delivered over the next three days as we explored one fascinating antiquity after the next, including the trip’s pinnacle, Somapura Mahavihara in Paharpur, a UNESCO World Heritage site. To our surprise we never saw another foreigner during our trip.

When we moved to Bangladesh in the year 2000, Bangladesh had a tourist motto: Visit Bangladesh before the tourists. We were feeling glad that we did, but also realize that Bangladesh is not on any tourism bucket list due to lack of tourism infrastructure and legalized alcohol. Tourism could help fund the needed excavations for which the government has little allocation, and by visiting, tourists could learn about the transformative influences of Bengal culture in Asia, Arabic and European countries. It’s a place worth visiting for history buffs.

On the way from Rajshahi to Bogra we stopped at the village of Puthia which has the largest number of historically important Hindu structures in Bangladesh. At one stop, we were swept away by a magnificent but derelict Rajbari palace, Maharani of Puthia Estate. This is one of the country’s finest old Rajbaris palaces that were built in the 1700-1800’s. Rajbari, King’s house, is the name given to the mansions of the Hindu rulers over Bengal during the British Raj.

Chas told us that there are dozens of deserted and decaying palaces like this in Bangladesh. Some are still family-owned but deserted. A few are managed by the government. The Puthia Rajbari complex, built in 1895, included the palace, now a museum, and several breathtaking Hindu temples inside a moat and walled complex, built by a local Zamindar (governor). The Shiva temple, on the estate, is the largest Hindu temple in Bangladesh while the Govinda temple in the Rajbari courtyard is decorated with hundreds of intricate terracotta designs.

Smaller palaces and temples belonging to extended family were walking distance from the main palace, and in the midst of all these picturesque historical buildings, the village goes on about its business, stepping over sleeping dogs and threshing rice on the temple porches. At the time this palace was constructed, religious practices included a mix of Hindu, Buddhist and Muslim beliefs.

Just before our trip, Bronwyn was notified that the U.S. Embassy had re-opened the city of Bogura for American travel. Chas was delighted. That meant he could take us to the oldest archeological site found thus far in Bangladesh. It’s an urban complex that existed for almost two thousand years, located on the outskirts of Bogura. That left Katerina spinning to find overnight lodging. While a Disney-like holiday hotel exists in Bogura, erected by an extravagantly wealthy Bangladeshi, we opted for a quieter, more modest hotel with a great feature – a western shower- and a night of family games.

As we approached Bogura, our overnight destination, we came to remnants of the ancient walled city, Pundranagara Mahasthangarh, dating 4th century BC to 14th century. First, we walked over an expansive, unexcavated mound wherein lies Gokul Medh/Behula’s bridal chamber. More about this couple as the story expands.

The entire city was encircled by ramparts. About one mile of the wall is still standing and Chas was keen to walk it.

Within the wall we saw remnants of Buddhist temples, stupas, Islamic mosques, tombs, and a residential complex. Since 1993, French archeologists have been working on the site. A small museum holds important artifacts found thus far, including an inscribed stone from the 3rd century BC, other Hindu and Buddhist statues, terracotta decorative tiles showing folklore and nature, coins and beads, terracotta plaques and toys, and objects of daily use.

While we walked over the grounds, the villagers were wrapping up a day of celebration under an enormous banyan tree by a mysterious chunk of granite dragged in from far away over two thousand years ago. The gathering may have had something to do with National Language Day celebrations taking place across the country on the weekend of our trip.

National Language Day is important because one of the reasons that the Bengal region broke off from Pakistan after Indian partition in 1947 was that Pakistan established Urdu as the national language and Bengal citizens would then lose their native language, Bangla. The other reason for the bloody war between Pakistan and Bengal was the difference in the way the two regions practiced religion. Pakistan followed a strain of Islam similar to adjoining regions of Afghanistan and Iran. Bengal region was noted for its religious tolerance. While Islam was the dominant religion by that time, there were still many Hindu worshipers living in the region. Muslims and Hindus co-existed and while following one faith, also celebrated the legends and religious festivals of the other.

Chas gave us some background on the interesting rock under the big banyan tree that locals call Khodar Pathar Bhita (Mound of the Stone, Bestowed by God). The rock seems to be the giant lintel stone of an ancient Buddhist or Hindu temple of the city but, in local legends, it was delivered there miraculously by God. Both Hindus and Muslims from nearby communities’ worship at the stone, pure milk over it and stand on it with their bare feet. While the villagers may have been celebrating National Language Day, the site is often a gathering place for traveling Bauls and other mystics and musicians. Here's a video of local Muslims talking about the stone and performing rituals, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F8CdQxdzuQU. While the narrators are describing the stone and the site in Bangla, the visuals are worth a watch.

A few hundred feet from the stone we came to a well called JIAT KUNDA 'Well Possessing Life Giving Power'. Islam arrived to this region in many waves of conquering sultans and their armies traveling from Afghanistan from the 13th to 15th centuries. But the earliest seeds of the faith were often spread much earlier by adventuring Sufi Pirs or mystic 'saints' who are said to have found the first converts to the faith through the power of persuasion and the occasional use of magic. Luckily for us, Chas pulled the story of the well and arrival of Islamic faith to this region from his vast pocket of facts about Bengal history.

Mahasthangarh, the ancient walled city, became one of the one first centers of Islam in the area through the work of Shah Sultan 'Mahisawar' (Fish Rider), a Dervish, who as legend has it, traveled to Bengal on the back of a giant fish from Damascus. As the story goes, upon landing on the river bank of Mahasthan, Mahisawar approached the last Budhist king of the city, Parasuram, asking for a plot of land no bigger than the size of his prayer mat on which to preach and practice his faith.

After granting his request, the astonished king watched as Manisawar’s small prayer carpet miraculously grew to encompass a large parcel within the walled city. Manisawar's influence and the new Islamic faith quickly began to spread amongst the people of the town. Realizing the threat to his reign posed by the persuasive Islamic sage and his converts, King Parasuram turned against the Sufis and Islamic converts. At first, the Pir and his followers prevailed against the onslaught of the king's army, but King Parasuram had a magic trick up his sleeve.

Inside Parasuram’s palace was a magic well, which waters had the power to bring his fallen soldiers back to life. Chas told us this as we stared into the well. As the story goes, the tide turned and the Islamic Sufis were losing the battle against the Buddhist King. In desperation, the Sufi Manisawar concocted a last ditch plan- he tied a small piece of beef to a kite, flew it over the walls of the palace and into the well. Since Hindus believe that cows are sacred and do not eat beef, the magic powers of the well were absolved, Parasuram's zombie army fell back dead and the Muslims of Mahasthan prevailed.

On the drive back to city center we passed a cattle market wrapping up for the day. Happy buyers were carting them home and others were dragging the reluctant cow from ground into the back of a truck. We saw one cow leap into a truck. I had no idea that cows can jump.

To help us digest the history of the ancient walled city, we stopped by the museum of relics found in the walled city during excavation. but it was closed due to the national holiday. We went back the next morning but the person with the key to the museum hadn’t shown up. Perhaps too much language day celebration. We briefly walked around another section of the archeological site near the museum, then headed out for our next destination, the apogee of Chas and Katerina’s select tour of ancient ruins, which was half way back to Rajshahi.

As we left the Mahasthangarh citadel, we passed by a huge hill on the right, which looks natural, but is actually the remains of a colossal temple which has never been excavated by archaeologists. On its top lies the historic tomb of Mahishwar which is still an important site of worship/pilgrimage to his followers to this day.

Chas kept a close eye on his archeological map, eye-balling nebulous places off the main road that would be a shame to miss. Since the Bogura overnight was not in the original plan, the road from there to the main attraction was a different route than planned with awesome possibilities.

At one point, Chas told the driver to take a sharp right onto a raised, single lane that rose between vast hectares of newly-planted, emerald rice fields.

In the distance we could make out a wagon piled with mustard grains, some trees and village structures. We finally stopped the car at a small turn-around and walked, once it became too risky for the van to go further. Chas was eager to find an ancient step-well that was tied up in a Hindu legend about Lakhinder’s bride that he and Katerina had been railing about, because the places we had visited on this trip were sites where parts of the Lakhinder legend took place.

As the legend goes, a Brahman merchant refused to worship the serpent goddess, Manasa, the mind-born daughter of Shiva. Manasa retaliated by taking the life of Chand's youngest son Lakhinder on his wedding night. Thus began the epic battle between Lakhindor's newlywed bride, Behula, and the mighty Serpent Goddess. Behula resolutely carried her dead husband's body on a raft down the river to the great God Shiva, overcoming obstacles at seven 'ghats' or wharfs to finally compel Manasa to give back Lakhinder’s life. Apparently, if we followed Chas down this path through the rice fields we would find the ritualistic step-well where Lakhinder was brought back to life. Who would have guessed?

In a cluster of thick overgrowth of trees and vines we indeed found the Hindu ruins dating back to the second Buddhist Pala Empire king. Tiny, but beautifully ornate temples with terracotta tiles, dome roofs, and arched entrances were nestled in the lush unattended site. A few villagers walked up to say hello and showed us the brick steps deep into the earth leading to the ceremonial well, the very site that Lakhinder was revived. For the backstory of the legend, see notes at end of story.

Back in the van, we were heading to Somapura Mahavihara at Paharpur, one of three UNESCO World Heritage sites in Bangladesh. After a couple more stops at ruins of Buddhist monasteries (Bihar Dhap https://maps.app.goo.gl/9ZcYvYiACS9XPmWB9 and Vasu Bihar https://maps.app.goo.gl/yvLkbrwRG3fgy9RL7), we finally arrived at the Paharpur World Heritage Site in late afternoon. My experience in seeing it was similar to my reaction to Machu Pichu in Peru – I was speechless!

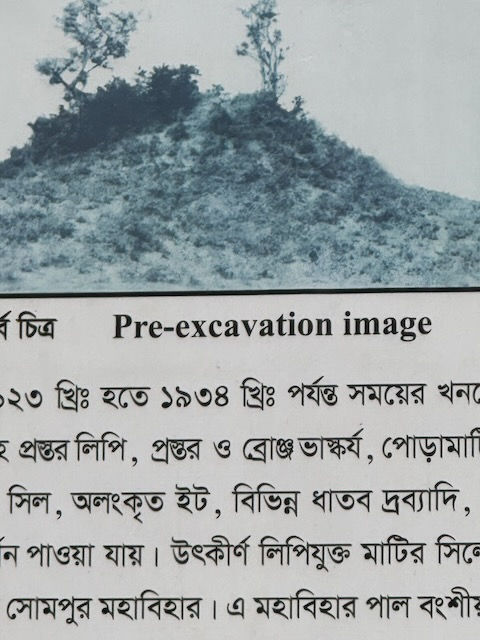

Somapura Mahavihara was the largest Buddhist Monastery (University) south of the Himalayas from the 8th to the 12th century and a center for learning for Buddhists, Hindus, and Jains. The ancient site, built by kings from the Buddhist Pala Empire, had a library of over one thousand books on religion as well as mathematics, astronomy, and other subjects. Scholars from across the Asian medieval world came to study there and wrote about the university. Abandoned after repeated attacks, the main monument eventually crumbled and was covered by dirt, looking like a hill, thus the name “Paharpur”. Excavations began in the 1920’s and 30’s, but new discoveries are still being made.

The protected Somapura Mahavihara monastery is surrounded by a fence. During the day it provides a popular outing for Bangladeshi’s living in the nearby village, as well as Bangladeshi tourists on a heritage journey from across the country. Just outside the gates, with a view of the ruins, is a tented area where locals hold family or village celebrations. A National Language Day celebration was in play as we arrived.

The thing that made our visit to this site so extraordinary was that Katerina, who knew Hasan Bhai, the caretaker of the archeological site, arranged for us to stay inside the museum complex in a guest house, which serves Bangladeshi diplomatic core, when in attendance. Behind the guest house there is a cluster of lodgings for archeologists, although no research is currently taking place. We were the only ones staying in the guest house and when the sprinkling of Bangladeshi visitors left and the gates were locked, we had the place to ourselves. Locked inside a Buddhist temple complex for the night is Chas’s idea of died and gone to nirvana.

The temple, constructed from bricks, is in the shape of a large quadrangle covering 11 hectares with monk’s cells (sleeping quarters) making up the wall and enclosing the courtyard. The monk cells had niches for their personal items and a brick pillar for meditation in the center of the room. The 20-meter high stupa rises from the center of the courtyard.

Visitors are allowed to walk around the lowest level of the stupa, which has one or two rows of terracotta tiles, each about 8 by 11 inches, depicting Buddhist and Hindu myths, local life, flora and fauna from a thousand years ago. Archeologists have recovered 2,800 terracotta tiles during excavation. The Bangladeshi government hired a ceramist to replicate originals and placed these along the bottom row of clay tiles that encircle the stupa. The thought was to protect the ancient tiles from vandalism. Original tiles were refitted on the upper levels of the stupa, which are off limits to visitors.

When Chas sees a fence, he wants to climb it and find out what lies beyond. In this case he longingly stared at the tile work and openings high in the stupa peak that are off limits. To his absolute delight, our guide, told us that once the visitors left, he would return at sunset and that we could climb and explore as much as we like.

Below Bronwyn is doing her own exploring.

When I expressed my fear of cobras, he told me that there were many snakes in the ruins during his childhood growing up in the adjacent village, but they are all gone now. Still….

As promised, Hasan Bhai returned at sunset and as the night blanketed the stupa he turned on the flood lights just for us. Wowee! Chas, Katherina, and Bronwyn climbed over the stupa, sticking their headlamps into every nook and cranny.

Eager for more time, Hasan told them he would return at dawn and they could have another hour or so to see the site, shrouded in morning mist, before the gates were open for visitors.

Then he took us over to a graveyard and another un-excavated section of the complex before having breakfast with his family. We ended our visit with a tour of the museum that holds some of the stone carvings and terracotta tiles that were excavated. Other relics are now in other museums in Bangladesh, including at the Vahendra museum we toured on our first day in Rajshahi.

The tourist police arrived as we were packing the car and shook hands with Charles. They asked about our visit. We thanked them for the honor of visiting such a monument.

We had one final day of exploration on our drive back to the airport. Chas directed the driver to another Rajbari palace, which is rarely visited by tourists. There were no admission fees and the palace was collapsing and secured by a metal gate. We could see its terracotta temples in the courtyard beyond.

Within minutes, a friendly villager came out to greet us. He was eager to show us around and practice his English. He sent word for his brother, the caretaker, to come with a key to unlock the iron gate across the palace entrance. He was a delightful fellow who told us that he had attended school in the abandoned palace back in his youth before a village school was built. He told us he was an English teacher in the local school.

His younger brother, the caretaker, has done a great job of cleaning up the debris and keeping looters and graffiti writers away, but they don’t get many visitors. On the day we visited, there was a big Hindu festival nearby, so several people had walked over to look at the old Hindu temples.

We enjoyed a fascinating tour of the fading grandeur, listening to local stories, and experiencing the deep friendship and hospitality of the locals. We followed our impromptu village guide through the entrance and into the first floor rooms. We warily climbed the collapsing stairwells up to the ball room. Stenciled and wallpaper remains from two hundred years ago can still be seen. The ballroom opened up into a now-treacherous portico balcony. It was easy to imagine hearing the voices, music and laughter from bygone days.

Like other Hindu Rajbaris, this Zamandar built himself a private temple adjacent to a lake or river that allowed for ritualistic bathing before prayer. Our guide showed us the stone steps down to the Zamandar’s wife’s bath. According to local legend, the Zamandar would hang anyone caught looking at his bathing wife. Apparently this king had a mean streak. For emphasis, our village guide showed us a terrifying dungeon and the hanging spot attached to the rear of the palace.

Delighted to have survived the tour before total collapse of the palace, we posed for photos with the small crowd of villagers. Our guide asked if we would like the use of a clean toilet before getting back on the road. He led us to a cluster of nearby houses, where his friend, a primary school teacher lived.

She welcomed us to come inside and insisted that we sit in the parlor and eat snacks while we waited our turn in the toilet. Again the crowd had followed us into her house and all delighted at her five-year-old son who introduced himself (in English) to us. What incredible hospitality we experienced at these palace ruins way off the beaten tourist path.

Closing in on the airport and not wanting our family adventure to end, Chas and Katerina pulled one last stop from their sleeve – one of the oldest mosques in Bangladesh.

Saturday prayers had just ended and the outdoor porticos by the river were vibrant with families.

Charles and Chas went inside and were awed by the massive stone work designs. Fortunately for us, Chas took some interior photos to share.

During this trip I came to understand how Bangladesh culture is a blend of Hindu, Buddhist and Islamic spiritual beliefs dating back two thousand years. While Bangladesh is constitutionally a secular state, it is a de-facto Islamic state today with about 90% population worshipping Islam and 10% Hindu. The religious history of Bangladesh is a study in ancient empires, and well worth a Wikipedia deep-dive. The colorful legends, beliefs and values of Islam, Hinduism, and Buddhism co-exist even today.

Bangladesh’s history and beauty unfolded as we drove along the rice fields of North Bengal and witnessed its dazzling architecture from ancient times. Twenty years later, we still came to Bangladesh before the tourists, but this time, with the help of Chas and Katerina, we really saw its magnificence.

We never fully appreciated its fascinating historical bounty while living there. So glad, thanks to our kids, that we had a second chance. From birth, and throughout their lives, our children have had the power to transform how we see what's important. From birth, and throughout their life, our children have had the power to transform how we see what’s important.

Written by Deborah Llewellyn

Deborah’s 3 Muses blog

April 2024

Credits and Historical Notes:

Photo Credits:

All photos taken by the author, her husband, Charles, and her children, Chas and Bronwyn, and Katerina.

Treat yourself to a video:

To add flavor to my story, treat yourself to this short film produced by Mohammad Imran Islam (Rafsan) for which there is a link on his Instagram site. You can feel his pride of country in showcasing and sharing Bangladesh’s natural beauty. https://www.instagram.com/reel/Czk8HwDIZK8/?igsh+MXVyYI¸zd2tOc-DZkw==

A little backstory on the snake goddess, Manasa:

In Bangladesh, after the scorching heat of 'grishsho', or summer, comes the monsoons and with it come welcome thunder, lightning and pouring rainfall. But, in rural areas, with the downpour, comes the menace of snakes that spread a pall of fear. Thus, all over the countryside, amongst the marginalized communities, be they Muslim or Hindu, householders organize performative rituals to appease the mighty Goddess of Serpents, Manasa Devi. Details of how this Hindu legend became celebrated and reenacted by Muslim villagers is colorfully described in this Daily Star Newspaper article, Of Monsoons, Myths and Manasa. While Bangladesh’s state religion is Islam, Manasa celebration provides a great example of Bangladesh’s blending of religions, as our family discussed throughout the trip.

I loved reading this and seeing the photos- the decoration inside the mosque is so beautifully carved! Your writing took me back to Bangladesh and to a trip I took with my parents when they visited, to some crumbling rajbaris and a buddhist monastery- perhaps it was Shalban near Cumilla. Of course it's also wonderful to see Chas and Katerina as well as the rest of you!

You took me on a trip. Thanks for removing the vail from my eyes about Bangladesh.

Thanks so much for writing this blog, Deborah. I love learning the cultures of other places and really enjoyed going with you vicariously. Sarah Maury Swan.

What an amazing adventure!….and even better…knowing the main “ characters “ in the journey!