The most peaceful method I use to fall asleep is to take a memory walk through a garden I have visited. With pillow fluffed and eyes closed, I attempt to follow the path as I walked it in order to see the trees and flowers that emerged around every bend. Knowing that I intend to revisit the garden through visual recall has strengthened my observation skills. It has helped me to develop the habit of being fully present in a garden so that I can go there again and again as I drift into sleep.

In late April, some friends and I visited several renowned gardens of Philadelphia and vicinity enjoying a delightful holiday and new material for my dreamscapes. I left those gardens with birdsong in my ear, the scent of spring jasmine and mint, the taste of dandelions on my tongue, blue stem flowers planted in my temporal lobe, and an heirloom tomato plant to nurture.

I walked on winding paths through waves of wildflower and cultivated plantings, sat on whimsical benches that could have been carved by wood nymphs. I grew in knowledge by observing these great gardens and listening to their gifted horticulturists describe their passions and approaches.

Each unique garden refreshed my soul while also tugging at my heart to return to my own garden in Beaufort, NC and get to work with renewed inspiration.

I was traveling with a group of gardeners, mostly from North Carolina, eight from Beaufort, NC, my hometown. One of our travelers was an award winning apple tree grower in Virginia and another gardener on the west coast flew out to see what us easterners were up to.

Our group leader was Adeline Talbot, Studio Traveler [atalbot@studiotraveler.com], who curates trips for lovers of the visual arts, architecture, and horticulture in the U.S. and British Isles. I traveled with her Irish Gardens tour in June 2023 and learned then how wickedly great her efforts to magic up the most unexpected offerings in her small group tours, places that few tourists see, all led by the most sought after guides who hold intimate knowledge of the garden and its secrets.

My friend, Penny Rule, and I took an Amtrak from Rocky Mount, NC, to meet up with the group at the Sofitel in Philly. Each evening, Penny and I discussed each garden as we dined. Then I figuratively packed it up to revisit again in my dreams.

This trip was a gardener’s delight. Let me take you along by sharing some of my photos and memories of the six gardens.

We visited Chanticleer and Stonleigh on the first day; Andalusia and Shofuso Japanese garden on the second day. On the second day, we also enjoyed an extraordinary lunch at Ellwood- a seed to table restaurant- hosted by William Woys Weaver, a Godfather of the native seed movement. On the final day, we crossed over into Delaware and visited Mount Cuba Center that serves as a base for Doug Tallamy, who founded the Home Grown Natural Parks Movement, and Longwood Gardens, a Disney World for gardeners.

Chanticleer

Adeline, our tour guide, correctly described Chanticleer as one of the great gardens of America with a beguiling intimacy that only adds to its charm. It has been called the most romantic, imaginative and exciting public garden in America…a study of textures and forms, where foliage transcends flowers.

Chanticleer was once a 50-acre country retreat built in 1913 by Adolph Rosengarten and his wife, Christine, of Merck pharmaceuticals. Two cottages were later constructed on the grounds as wedding gifts for their children. The cottage of daughter, Emily, now serves as the visitor’s center, office and classrooms for the 35 acres of public gardens.

The second cottage for son, Adolph Rosengarten, Jr., was destroyed by fire and the ruins have been cultivated as if a set on a stage. In one interior corner, a fountain provides sound effects and the stone faces emerging from the depths of the water seem to sing. The stone remains of the son’s cottage embrace the weeds, cultivated vines and flowers. Visitors are lured inside, left to wander and to wonder, to hear voices from the past enshrined in the remains of the manse.

Chanticleer is a pleasure garden. The glorious visuals of varied landscapes joined by paths though forests and meadows, studded with whimsical benches, invite the walker to slow down and take it all in. An elevated walkway provides stunning views of the property and access for visitors with disabilities.

There is a pond garden, woody herbaceous gardens that focus on the visual impact of foliage, a vegetable garden that celebrates the beauty of agricultural crops, and a cutting garden to produce flowers for arrangements.

The tea cup garden and terrace garden that feature seasonal plants in array of clay pots. I was certain that Peter Rabbit would emerge from behind a pot of tulips or geraniums. After all, it was a storybook setting.

Chanticleer has brought solace to those in need. One writer, Margo Rabb, describes a difficult transition in her life after her husband lost his job in Texas. Displaced and dispirited, they moved to Philadelphia. Straining to adjust to a cross-country move, while also dealing with lingering grief from her mother’s death, she began to visit the Chanticleer garden. Not once, or twice, but every day. She wrote a story describing the transformation in her life wrought by this garden in a New York Times article, Garden of Solace, which you can access at https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/05/opinion/garden-of-solace.html

Chanticleer is also a place to learn. Visitors have the rare opportunity to question the eight horticulturists found throughout the gardens at work on their individual patches of turf. Each gardener is responsible to design, plant and maintain an area of the estate, with the assistance of other gardeners and grounds crews. It is a work of art and science. You will not find the horticulturists bent over their weeds like a farmer with sweat on his or her brow, but appraising every placement of leaf texture, flower color and seasonal impact like a discerning painter. They are delighted to answer questions.

At Chanticleer, I saw what I’ve noticed in other highly regarded public gardens. The Foundation hires the best people and empowers them to show their unique skills and talents through their own designs, with the understanding that they will also work as a team toward a shared philosophy and ethos. The eight horticulturists work individually on their gardens and as a team for overall effect. These factors combine for stellar results. Each area is figuratively stamped with the horticulturist’s names, along with the teams of gardeners and groundskeepers who assist them.

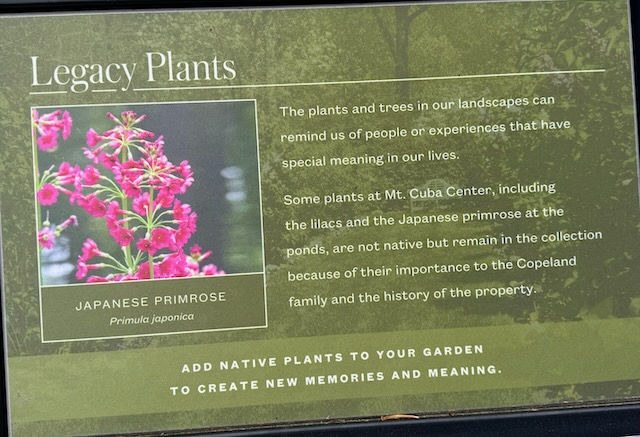

The overall garden is an invitation to find tranquility, take pleasure, and depart empowered to replicate something of its message in one’s own small plot back home. They teach visitors to design with nature and for nature. Examples include cisterns that capture and reuse rainwater, integrated and organic pest management, lawn alternatives to turf, and replacing invasive exotics with native trees and plants. The exception being the legacy plants-those given to the family marking significant occasions over the course of the family’s history.

Each area of the 5,000 plant garden contains an artfully sculpted wooden or stone box with a clever door and latch. Open it to find laminated flower charts of plants found in that vicinity of the garden and propagation instructions. The boxes are so adorable that it is impossible to pass without opening each and learning from the cards. In Chanticleer’s case it is not only the plantings that draw the visitor to linger and learn, but also the art.

I was dazzled by the gardens and scintillated by the porch and garden furniture. The benches and gates at the entrance are works of art.

The porch furniture and garden furniture are brilliant in their conceptualization, whimsy and actual comfort. On the porch, Adirondack chairs, hold wooden cushions fashioned to look like plush ones. Giant wooden Adirondacks in bright colors are placed in distant meadows. Stone sofas are crafted to look like upholstered sofas. The arm of one sofa held a TV remote control replica made in stone. The show, to watch from the stone sofa, is Chanticleer, itself.

I did not want to leave and would have been happy to start and end our tour right there, but luckily there was more to see. Off we went to tour Stoneleigh.

Stoneleigh

Stoneleigh is a 46-acre garden near Villanova University. The garden blends history, horticulture, ecological and conservation values. Free to the public, it teaches visitors the role that indigenous plants fill in helping our environment. The experience renders a sense of serenity to all who come. The website is: https://stoneleighgarden.org/garden/home/

Like Chanticleer, Stoneleigh was a summer home for a wealthy family escaping Philadelphia’s summer heat and viral pandemics. The Edmund Smith family purchased 65 acres in 1877 and built a home, that is now used for staff offices and training. The Initial gardens were developed by Charles Miller, who trained at Kew Gardens. The Samuel Bodine family purchased the property from the Smith’s in the 1900’s and built a Tudor mansion that also stands today. They expanded the formal gardens but became dissatisfied with the effect. The Olmstead Brothers landscaping firm helped them to redesign the gardens over fifty years into a more pleasing environment using a naturalistic approach.

In 1932 the Otto Haas family purchased the property and began a multi-generational tenure of the home and grounds. The Otto family also appreciated the Frederick Olmstead’s approach to landscape gardening with attention to vistas and natural landscapes, especially tuned to its positive effect on the viewer. With that commitment, the Haas family placed the property under a conservation easement in 1996 and transferred management to the Natural Lands Foundation with free access to the public.

The gardens are managed by only 8 full-time employees, including 4.5 horticulturists and an army of volunteers. Since taking stewardship, the Natural Lands staff has planted over 100,000 plants.

When we arrived, they were setting up for a plant sale, one of the ways that they fund the garden. We had a lively docent, who is the education outreach staff member. My favorite quote from her tour around the grounds was, “We like to redefine what a weed is.”

The most interesting features in the Stoneleigh gardens, to me, were the dead trees. Our guide explained the importance of dead trees to insects and nesting birds. At Stoneleigh, hired or volunteer sculptors shape the trunks, branches and crowns of dead trees on the grounds to meet the needs of birds and insects. I also liked the bog garden and appreciated how the horticulturists are adding natives to old established gardens, demonstrating for visitors how to make a transition from formal exotics to native plants in their own garden.

Take a tour for yourself on this YouTube video: https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=Stonleigh+Gardens#fpstate=ive&ip=1&vld=cid:8a15795e,vid:-1O_bGoQUAc,st:0

Andalusia

Andalusia holds much appeal for American history buffs. Inhabited from 1790 to 1970, visitors can trace the contributions of early American aristocracy to architecture and garden design. The home was first built as a getaway from the yellow fever epidemic in the city. As popularity grew for living in the country, enabled by easy accessibility provided by the railroad line, so did the expansion of the Greek Revival home and its array of outbuildings. Check it out at: https://andalusiapa.org/historic-house/

With its soaring white columns and superbly crafted interiors, the mansion at Andalusia—called the Big House—is considered one of the finest, most distinctive examples of Greek Revival architecture in the United States. Dating from the 1790’s, the story of Andalusia parallels and reflects that of the nation itself. Visiting this National Historic Landmark is a journey back in time, an invitation to see firsthand the traditions and tastes of the generations of Biddle family members who called it home.

The house was a bit formal for my tastes but there were interesting features within, such as the bed of Napoleon’s brother, and other gifts he gave to the Biddle’s when he returned to France. The library was awesome. I wanted to climb up the ladders and check out the collection, grabbing a few to pull down and curl up with on a reading sofa.

I loved the charming outbuildings down by the river, one for the men to shoot pool and play card games while they sampled the wine cellar, and the other for women to chat and drink tea in the afternoons. These caught my imagination and I wondered what went on behind closed doors. It was also interesting that the visitor’s center toilets were designed from the original outdoor privies and showers for men and women.

The initial owner of the home, John Craig, was an avid gardener, as evidenced by his copy of the 1791 book, Every Man His Own Gardener, where he listed on the back page the many varieties of flowers he planted. The current gardens date back to Craig’s gardens planted 200 years ago.

Other residents added small touches, and sometimes extensive changes to the garden. In 1888, Letitia Glenn Biddle, noted in her journal that vegetables, rather than flowers, were mainly cultivated in Andalusia’s gardens. She set out to redress the balance, adding colorful blooms including tulips, hollyhocks, larkspur, gladiola, and a lovely “American Beauty” rose cultivar.

Letitia’s horticultural expertise didn’t just serve Andalusia, but the nation as well. In 1904, she hosted the very first meeting of the Garden Club of Philadelphia at Andalusia. Nine years later, she and several other women, working in the men’s billiard room, drafted the by-laws that established the Garden Club of America. Other significant changes to the gardens in the 20th century include work by her grandson James “Jimmy” Biddle (1929-2005), who planted the original Green Walk in the 1960s and White Garden in the 1990s.

The most recent transformation of Andalusia’s gardens took place in 2017-18, when noted British landscape designer Arabella Lennox-Boyd stepped in to update them. Lady Lennox-Boyd’s familiarity with Britain’s stately homes made her ideally suited for creating an appropriate natural context for the Big House, while her flowering design style perfectly complemented Andalusia’s existing gardens. Lady Lennox-Boyd added some 14,000 plants — assorted trees, shrubs, roses and perennials.

She added magnificent herbaceous borders, often color-themed.

Andalusia’s gardens contain many varied and interesting areas.

My favorite was the old ice house. Lady Lennox-Boyd envisioned it as a snow-capped mountain with abundant blue-star juniper across its roofline and an arbor swathed in white wisteria. An old walled garden along the greenhouses provided protection for plants that may not have over-wintered, a technique borrowed from Irish and British gardeners.

For the most part, the plants are of an exotic nature with a few native plants sprinkled about, such as the little bottle-brush buckeye. Many of my fellow travelers were drawn to the pet cemetery which is reached by walking down the Woodland Walk, host to thousands of daffodils in early

spring.

Lunch with William Woys Weaver

Many in our tour group strive to plant with natives so it was a rare treat to have lunch with William Woys Weaver. The food was prepared by Adam Diltz, Elwood Restaurants chef.

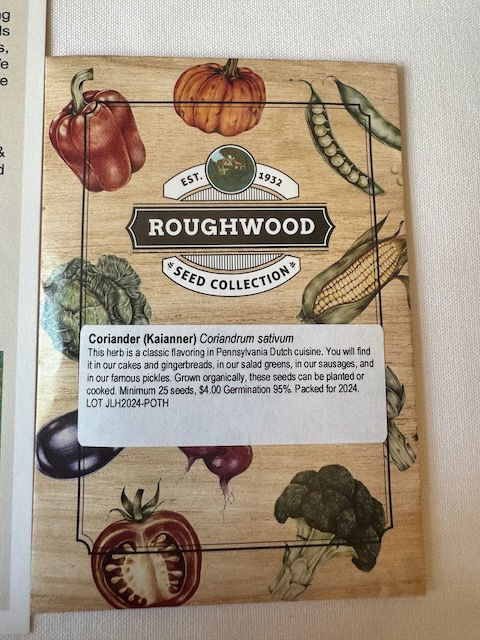

For three decades, Philadelphia-area native, William Woys Weaver has been a leader in promoting and preserving heirloom vegetables through seed saving and garden design. To showcase the flavor and delight of his work, Dr. Woys Weaver partners with Chef Adam to host meals focused on the truly native cuisine of the region, a seed to table culinary experience. Learn more about Weaver’s work at Roughwood Center for Heritage Seeds https://www.seedways.org/.

Weaver gave each of us a packet of coriander seeds and a tomato seedling, Peg O’ My Heart, to take home. He told us that the fruit from this tomato weighs a pound and that when Roughwood center propagates enough plants and seeds, this tomato will become the rage for vegetable gardeners. The mission statement on the seed packet is worth quoting:

At Roughwood, it is our commitment to explore our cultural heritage expressed through the garden. It is our responsibility to care for these seeds and the stories and cultures that accompany them, and bring them to present use and memory. Food and seeds both are edible folk art. Through these actions we can create a more interestingly diverse, nutritious, and delicious world.

Growing the Peg O’ My Heart Tomato

The history of the plant, according to Google, is the following:

Fifty years ago, while teaching horticulture, a student gave Peg Davis four seeds of a tomato that her grandparents had grown in Pennsylvania. This was my family's tomato from my parent's own garden, she told Davis. The student's family was German, the root of the seed, says Davis. Through extensive work over many years Peg grew the specimen and propagated the seeds into bountiful tomato harvests. It was accepted into an heirloom seed bank in 2023. Read Peg Davis’s story at the following link: https://www.newsleader.com/picture-gallery/news/local/2023/09/06/heirloom-tomato-peg-o-my-heart-seed-savers-exchange-snow-spring-farm-va/8376512001/

We walked away from lunch proudly carrying our attractively packaged gift and took extra care in getting it through airplane security or tucked carefully into trains or cars for our return travel. We all laughed and shared anecdotes about the journey, feeling a shared obligation not to let it die. Back home, there were varied levels of success in bringing our heirloom plant to fruit. Mine died from poor drainage. Several others reported that theirs died or was stalky with no production.

On their way back to Beaufort, Lisa and John Dunson stopped in Edenton to visit a mutual friend, Kent Brondel, who used to live in Beaufort and has a green thumb. The Dunsons’ gave one of their two plants to Kent thinking he would have more luck getting it to produce than they would.

Kent took on the challenge, but just as he was ready to pick the first tomato, a creature ravaged it in the night. Hidden cameras later identified the culprit as a groundhog who ate the baseball size first tomato, then started in on the branches. Not to be defeated, Kent put the hacked off plant in a bigger pot with organic soil, and put the pot on a pedestal with an obelisk cage, and a hidden security camera. He is happy to report that it is now 4 feet tall.

Photo of Kent's tomato

John Phillips, one of our trip mates, along with his wife Mary, took the mission to another level, somewhere between passion and obsession.

Mary told me that John spent hours studying how to grow a tomato, resulting in healthy Peg plants and then he began to propagate. From the first two plants he grew nine more, with five more seedlings now ready to plant using a different method. I wanted to see his plants first hand and to hear what he did to achieve such successful results.

Notebook and camera in hand I asked for an interview. First he told me a funny story. When he and Mary were married thirty-seven years ago he planted two tomato plants for the love birds. They grew 12 feet tall and never produced a tomato. So when William Woys Weaver handed them the two Peg O’ My Heart seedlings he and Mary looked at each other and laughed. This is not going to go well, they whispered to each other.

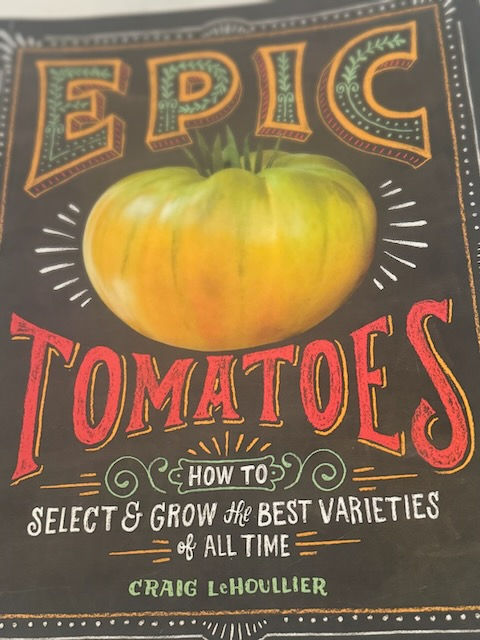

But then John got the zeal and determination to make these a success by studying how to grow tomatoes. He then showed me his “Bible” – Epic Tomatoes- How to Select and Grow the Best Varieties of All Time, by Craig LeHoullier, who is known in Raleigh, NC, as the tomato whisperer. John said he bought the book and read a chapter a night.

Then he showed me their two original plants, now laden with tomatoes. They are planted in 9-gallon, heavy duty plastic pots on the south side of his house, where they receive all day sunlight. They’re healthy, tall plants with an abundance of flowers and tomatoes staked up with various methods. But he was determined to go further with his project.

He went on to learn more about the planting and care of his growing plant which he has applied to nine cuttings in 10-gallon heavy duty plastic pots (ordered from Amazon), each with 2-3 inches of river rock in the bottom. These are growing on the North side of the house getting morning and mid-day sun. These plants are supported by some nifty, attractive, snap-together tomato cages that can be disassembled at end of growing season to keep and re-use for next spring. He purchased these at https://www.thespruce.com/best-tomato-cages-5324239All John’s pots are topped with pine straw to slow evaporation.

Here are some tips John shared:

Look for the main stalk of the plant, pull off branches that are sapping energy from the main stalk.

Look for leafy limbs. Suckers sprout off of these. Cut the sucker off to propagate.

Buy some ten-gallon heavy duty plastic nursery pots. Add 2-3 inches of river rock and thoroughly soak the rocks. This is training the roots to grow downward, seeking the water in the rocks. Make sure water freely drains from the pot.

Add soil. (He used Daddy Peat’s Potting Mix.) Poke finger into the dry soil and add the sucker. Then water and mulch with straw. All nine suckers grew into plants.

Water these only when it feels dry to a finger inserted in the dirt, generally about twice per week. Water until the water runs freely out the bottom. The pine straw is critical to slow evaporation.

He has now tried rooting five plant suckers in water and these are doing well. However, he is pleased with the method of just sticking the sucker in the dirt. The reason he is growing so many plants is to be able to harvest the seeds to plant next spring.

This is what he learned about harvesting seeds.

Cut the tomato in half.

Squeeze out the juice and seed into a cup. Let it set for 10 days. Be prepared for bad smell.

The seeds will separate and go to the bottom. Strain the water to save the seeds.

After drying the seeds, over-winter them in airtight jar such as medicine bottle. Others use a paper coffee funnel liner. Fold over tape and label.

I asked John the cost of his eleven plants. His initial outlay was $280 of which $230 can be used over multiple years – pots, river rock, and tomato cages.

I have high hopes that next summer John will share seedlings and tips, giving each of his fellow travelers a second chance to save our heritage through a tiny seed.

Shofuso – A Japanese House and Garden

After lunch at Ellwoods, we visited the Shofuso Garden, which reflects the history of Japanese culture in Philadelphia and provides a wealth of ideas for landscaping for serenity. The Shofuso house was initially built in Nagoya, Japan, using traditional materials and methods. It was then transported to the Museum of Modern Art in NYC. Finally, it was moved to Philadelphia and reconstructed in 1957 at a site used to showcase Japanese gardens during the 1876 Centennial Exposition. Today this area is known as the Fairmount Park National Historic District.

The house and garden are owned by the City of Philadelphia but is preserved and cared for by the Friends of the Japanese House and Garden. The non-profit raised $1.4 million to restore the Hinoki bark roof. I was awestruck by this news, as I inherited a Hinoki tree as part of the front landscape on our Craftsman home. Now I know what to do with its bark. The non-profit also constructed a garden restoration in 2016. After completion, Shofuso was named the third-ranked best Japanese garden in North America.

Mt. Cuba Center

On the third day, we visited Mt. Cuba Center Gardens, located in Hockessin, Delaware, just over the Pennsylvania border. Mt. Cuba offers garden bathing at its ultimate with stunning vistas, intimate woodlands, and lush meadows putting the beauty of native landscapes on display. Check it out at mtcubacenter.org.

Mt. Cuba is the go-to resource for planting native gardens. Their trial gardens were attractive and fascinating. The purpose is to research which varieties of native plants are the most powerful pollinator attractors.

The center does this by planting all the hybrids of a native plant and assigning volunteers to sit during specified hours and count the insect pollinators that visit this particular variety. Results are available in beautiful pictorial booklets for purchase or on-line for no cost. So if you want to plant perennials, check out Mt. Cuba’s website to learn which variety has more bang for the buck.

Mt. Cuba had one of the most interesting and beautiful gardens I’ve ever seen, showing what you can do with native plants which are so critical for our future due to their importance as pollinators. As the entomologist, EO Wilson, is oft quoted, Insects are those little things that rule the world.

Mt. Cuba offers many classes and events to attract visitors, and encourage casual picnics, nature photography, bird watching, meditation, story time, yoga, family fun and garden crafts. As visitors join these fun events they are also inspired to plant natives. The center has many vehicles to learn why and how.

Mt. Cuba center serves as a laboratory and staging ground for the work of Doug Tallamy, our national torch bearer for changing how Americans think about planting their yards. Tallamy, a professor of Entomology and Wildlife Ecology at the University of Delaware, through his on-line videos, lectures, and books, has led one of the greatest conservation projects of our time, taking back our future, one yard at the time.

He encourages us not to be discouraged by the diminishing numbers of butterflies and bees, but to plant our own garden to attract them, and then to encourage our neighbors to also do so, creating a corridor, along which these beneficial insects can feed and procreate. If we save the natural world, we are saving ourselves. Each person contributes and in doing so becomes part of a Home Grown National Parks movement.

One of Tallamy’s key recommendations in his book, Nature’s Best Hope, is to shrink the lawn and plant native flowers, shrubs, and trees instead. Having read this, I was surprised to see a sizeable and nicely cut lawn at the Mt. Cuba Center.

When asked why they have this grassy lawn, our guide laughed and explained. We believe that a lawn is useful if purposeful for sitting upon. We use this space for picnics and classes. And if you look closely you will see that the green is actually mowed weeds.

He told us that in the U.S., Americans use insecticides and weed killers to eradicate native weeds that are bringing balance to the soil. Then we add fertilizers to make up for what we have just removed. Mt. Cuba, like Dough Tallamy, teaches us that nature’s best hope is each of us. Conservation starts in our own garden.

Longwood Gardens

I visited Longwood Gardens (founded by Samuel DuPont in 1921) in my early twenties. At that time, I was amazed at the eurhythmic gardens, huge beds of plants artfully laid out for visual effects. However, by the end of the day I was exhausted from the endless brick walks and stadium like greenhouses. These were formal gardens, an American Versailles, of sorts. They were spectacular but lacked soul. A Disneyworld for gardeners who are thrilled by exotics.

Fortuitously, Adeline, had arranged a guided tour of the greenhouses. We were lucky because the skies darkened and the rain was about to set in. Our Longwood guide whisked us around the long entrance lines and up to the greenhouse, rushing to beat the rain. Just before entering, she pointed out several gigantic pots of conical flowers and told us this: Longwood’s goal is to create “floral fantasies.”

The Tower of Jewels, in the borage family, native to the Canary Islands depicted her point. These photos give context for plant size and the beauty of the blossoms close-up. Indeed, these towering pots of jewels might be described as floral fantasy.

Our first stop, the bathroom corridor, had walls lined with 33,000 ferns, intended to soothe anyone waiting in line.

Many Longwood plants were presented in mass. For example, the delphinium beds of 200 plants, with other varieties of the same plant in the same bed, or two-three hundred orchids on display out of 6,000 orchids in the collection. Other plants were one of a kind stand-outs.

Our guide said this: Our 120 horticulturists make every plant do what we want it to - color, height, bloom, etc. It takes two years to create a tree geranium that looks like a lollipop. We manipulate your expectations.

If you expect something to be small, like a daisy, we may shape it into a tree. We transform hydrangeas from shrubs to ground cover or gather them in huge hanging baskets. We are accustomed to seeing a hanging basket with one plant; our massive hanging baskets hold thirty plants.

She went on to say this: Even though we only close three days of the year, the visitor never sees the transitions of plants and bed makeovers. All they see is eye candy.

After we were released to wander the grounds, map in hand, it started to rain again. Some battled the rain with umbrellas. Wet and chilled, I went to the gift shop, abundantly supplied to fill a gardener’s fancy. Lovely place with beautiful gifts for those who love to design, plant and decorate garden spaces. I bought interesting gardening books (Fifty Plants that Changed the World), a recipe collection for botanical mixers for my daughter who is the cocktails queen, and napkins for outdoor dining now that my butterfly garden is in bloom and the river birch tree leaves are creating light and shadow patterns on the garden table.

All Good Things Come to an End, Maybe…

Riding back from Longwood Gardens to our hotel in Philadelphia I reflected on my favorite gardens – Chanticleer on the first day and Mt. Cuba Center on the final day. I loved these gardens because they designed with nature and showcased perennial flowers, and native trees and shrubs that feed and host pollinators. They were landscaped to capture the terrain, weaving in and out of forests and meadows, providing spots at every turn of the path to rest and inhale the gentle beauty.

The curators of Chanticleer and Mt. Cuba gardens also allayed the guilt of visitors who have a few non-natives or exotic specimens in their own gardens. Perhaps it’s a garden in transition from formal to native, or one that includes gift exotics from a friend or loved one, or something that blooms so beautifully you couldn’t resist buying and planting it.

As we walked through my favorite gardens, our guides pointed out non-native trees and shrubs and told us why these were meaningful to the families who once lived here and kept for these reasons as they transformed the gardens from formal to natural and native. The non-native plants provide minimal support to wildlife, but they are linked to family memories, and love.

The guides showed us how to use pots for pops of seasonal color, such as tulips, which are non-native and no benefit to pollinators, while keeping the flower beds for host and nectar plants for butterflies and bees.

Still, three months later, when I lie down at night, I choose a garden from this trip to revisit. I start at the beginning and stroll those paths as I drift into sleep. I have the six gardens from this trip and a dozen from the Irish Gardens tour.

Some nights I imagine being in the Sara P Duke Gardens that I visit when back in Durham. I remember reading and picnicking on the grassy meadow beside my first love, and later watching my children climb the magnolia trees, dance around the pond, and hide in the arbors, just as I did as a child. Recently I took my Australian friend, Kate Ramsay, to Duke Gardens to walk off jet lag from her long journey. I showed her areas in the garden that hold my memories.

Throughout my adult years, my mother and I made a spring visit to her cousin Joyce Lucas’s vast country garden. As I drift into slumber, I return to Joyce’s garden with my mom. What a joy to remember those visits and the stories my mother and Joyce told about digging up plants from wayside ditches along a country road as Joyce gave us the grand tour of her vast gardens, showed her prized plants, and moaned about the voles eating everything she’s got.

When I wake each morning, I take a cup of coffee to my garden and visit every colorful flower and leafy, green plant, realizing that I start and end my day with gardens.

What a blessing.

Written by Deborah-Llewellyn.com/blog

Beaufort, North Carolina

Write to me at: deborah.llewellyn@gmail.com

All photos were taken by the author.

Comments