What's So Great About Birding?

- Deborah Llewellyn

- May 31, 2021

- 15 min read

I have a steep learning curve to identify the backyard and seashore birds that roost, feed, chirp, and soar within a block of my house. I am ready to meet the challenge, armed with the perfect beginner's book on NC birdwatching and several birder friends to encourage me. So, what's so great about birding? I'll take a circuitous route to answer the question. After all, this is a traveler's tale.

In 1997-2000, we lived in Falls Church, VA after postings in Peru, Bolivia, Ghana and Nepal. I had learned to be dazzled by my environments so took in stride that there were things of wonder even in the USA. One day, I looked out the front door and was amazed to see this beautiful flock of birds on the front lawn, glossy black with shimmers of purple and lime green. I called to my husband to come quickly to see this wondrous sight. He looked at me in dismay and said, "Deborah, these are common starlings like crows, considered a pest." He walked away shaking his head.

I avoided any further remarks on bird sightings until we settled in Beaufort, NC, a small seaside town, in a house with a lush back garden that attracted birds. I discovered the male Painted Bunting, which has a royal blue head and shoulders, a cherry red belly and eye ring, lime green upper back and olive green wings.

Ten years ago we had a sighting or two, which I mentioned to my botanist neighbor, Sue, who lives on the next block. She nonchalantly replied that several buntings come to her garden every afternoon about 4:30. I was determined to lure her painted buntings to my garden.

I innocently inquired what she did to attract them. She said that painted buntings come to bird feeders with easy access to a shallow watering dish set on the ground partially hidden by ferns, hosta and leopard plants, with shrubs and small trees where they can dart when frightened.

She did not tell me another secret ingredient. They eat only white millet seed which is expensive and not easily obtained- but we found this out from the owners of Edgewater Gardens who have four or five buntings, year round. So we set out to build the landscape and lure Sue's birds from her block to ours. Ten years later, we now have buntings in the morning hours and again in late afternoon. In April I saw a lime green female bunting for the first time. I have delicately avoided the topic of painted buntings with my neighbor, Sue.

So at this point, I knew the common grackle, starlings, painted buntings and the absolutely base common birds of cardinals, robins, doves, humming birds, blue jays, crows, the Red bellied woodpecker, ducks, seagulls and egrets. In early April I came across a birding book, North Carolina Bird Watching – A Year Round Guide, by Bill Thompson, III, at my local library. I checked it out and renewed it three weeks later. It was part of a series, a book per state, developed by Bird Watchers Digest about twenty years ago.

The book was perfect for me. Unlike the birding books stacked by the binoculars on our window-side table with hundreds of sketches and elaborate descriptions, this one has a large photo of one bird per page, with basic characteristics that will help the viewer distinguish differences between birds of the same species, such as house sparrows, chipping sparrow, white-throated sparrow and song sparrow.

It covers the most common birds seen across NC., with an addition of ten unusual and beautiful "must see" birds, worth the "hunt."

I decided that this book would enable me to establish backyard bird identification as a new goal for this birthday year, along with learning to fish, which is another story. So for my birthday, I requested a proper (pretty) fishing pole and (flashy) tackle in order to troll for fish from our sailboat, and THAT BOOK!

Charles, being a doting husband, turned to Amazon to purchase the book and discovered that it is out of print and considered a rare book that can only be purchased, used, for $880-$1,000. I was disappointed, and said no matter, I will just keep renewing the book. On my birthday, May 8, I opened a package from Charles and to my delight found the birding book.

He had inserted the printed page from Amazon, just inside the cover, to remind me how costly the gift. He said, "No amount is too high if it is something you want," but his sly grin indicated he likely worked his network to get the book for me and paid nothing of the sort. Never mind, Charles is a keeper.

So now I've started my own little graphic journal to sketch sightings and record what I am learning. I watched two inspirational films: Birders- The Central Park Effect, and The Big Year, a comedy about birders competing to sight the most birds over one year. Along the way, I talked with my Beaufort birder friend, Stan Rule, and also touched base with an old friend Neil Baker, who developed the Tanzania Bird Atlas, out of his lifelong birding passion. And finally I consulted my daughter, Bronwyn, who always has a lot to say about wildlife conservation, and is an avid birder herself.

Since childhood, Bronwyn has loved all creatures great and small. Bronwyn says, "Birding is a gateway drug to becoming a naturalist, because it is so accessible whether living in the city or country." She developed some keen birding skills as an undergraduate in her study abroad program in Kenya – The School for Field Studies. One course exam required identification of 200 East African birds by sight and sound.

As an Environment Officer with USAID in Nepal and Tanzania, she came across some avid birders and projects. She began to see how birds are a major indicator of the health of our planet. Through the "Citizen's Science Movement," amateur naturalists, including birders, use apps to contribute data that is useful on a global scale to track the health of a species, migration patterns, and climate change. Through birding, ordinary citizens discover a way to participate in something larger than themselves.

A good website for citizen scientists is https://ebird.org. It transforms your bird sightings into science and conservation. BIRD, sponsored by Cornell University, helps birders to plan trips, find birds, track lists, explore range maps and bird migration. The 750 million observations submitted to eBIRD have contributed to development of 500 bird migration maps.

After graduate school, Bronwyn had the opportunity to work with a renowned birder, Neil Baker. Neil migrated to Tanzania from England as a young man to work for TANESCO. He married Liz Baker a British citizen who grew up in Tanzania.

Together, Neil and Liz developed the Tanzanian Bird Atlas from 1985-2021, which can be accessed at http://tanzaniabirdatlas.ne. Neil has photographed thousands of birds in Tanzania with the purpose of identification, discovery of unrecorded species, and to track migration patterns and environmental changes that expand or contract a bird's range.

Liz and Neil discovered a challenge, which they tackled in a unique way. Children in coastal Tanzania have little to do for entertainment, so killing birds with slingshots is a popular activity. This problem also exists in many other locations around the world, often those with rich, exotic bird populations. Killing birds for sport or feathers is contributing to extinction of some of the most beautiful bird species.

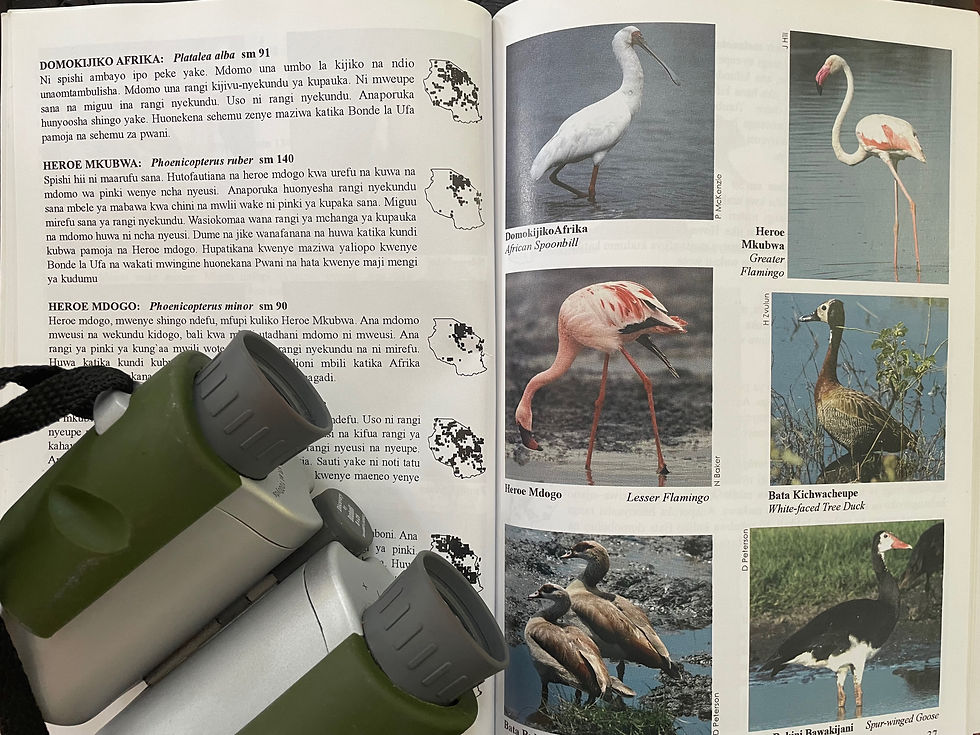

Neil and Liz pursued funding to develop a bird book with colorful photos for kids that could be printed for $1 and distributed freely to thousands of Tanzanian children who attended birding clubs organized by Neil and Liz and other kids' naturalist's programs such as Jane Goodall's "Roots and Shoots."

According to Bronwyn, "Children's birding projects get kids interested in the world around them. Often people who live in nature don't have an understanding of its uniqueness. It takes only an experience to open people's eyes."

Bronwyn saw first-hand how a birding book, written in local language at children's reading level, is a key tool for conservation, by getting people to care. As a graduate student, she was working with the national park service in Bhutan. Bhutan does outreach to local secondary schools near the park headquarters.

Bronwyn organized a birding morning. She and the rangers borrowed as many binoculars and bird books as they could find, and invited the kids to join them at 5 am for a bird walk. They divided the kids into groups of eight, one ranger, one or two pairs of binoculars and some bird books. They took a walk and when they spotted a bird, the kids had to look it up in the bird book. The teens got very excited with the books, arguing about whether it was this one or that one, trying to identify the differences. These were birds in their backyard, ones they had seen and barely noticed. It was the bird book that made it a game.

As a USAID environment officer, Bronwyn met a man in Nepal who grew up in the tropical region of Chitwan. He told Bronwyn that as a kid he had a slingshot that he used to kill birds. "It was my fun activity." He was given an opportunity to join an environmental club in school and learned about birds and how unique they are. At club meetings they were able to look at birds with binoculars, and from attending the club, he developed a strong interest to study birds. As a young adult he got a job with Tiger Tops Safari Company leading bird walks. He loved the work but had a passion to do more to address bird extinction.

He learned about the problem of vulture extinction. Vultures are dying from targeted killings by people who consider them dirty or by animal poachers, because vultures show animal wardens their location. Vultures are also killed for use in traditional medicine. Another cause of death is the anti-inflammatory drug, diclofinic (found in Votarin) given as a last resort to sick animals, especially cows in Hindu areas of South Asia, that usually die anyway.

Vultures die if they eat these dead animals, whereas the drug does not kill other scavengers such as rats and dogs. In India the population of vultures has plummeted by 90% with an estimated cost to the economy of around $3 billion per year. Not having vultures eat animals that die of disease means the disease can spread and lots more animals get sick and die. Cases of rabies rise as well as the rat and dog populations spreading livestock diseases by bringing the tainted meat back to human settlements.

The topic of vultures helps us see how even the ugliest of birds is critically important. Diseases cannot survive in the vulture's digestive tract, which means that as they eat dead animals, they stop the spread of diseases. When you lose vultures, rats and dogs and other pests fill the void and these do spread diseases from the dead animal. This young Nepali man has been able to actualize his creative dream of opening "vulture restaurants" where vultures are fed with clean food in order to secure continuation of the species.

I was beginning to see how birding was not just entertainment but also serious work to save the planet. From talking with Bronwyn, I developed renewed respect for our friends Neil and Liz. Neil has since retired and, sadly Liz passed away. Neil continues to live in Tanzania on a retirement visa. He focuses his days on expanding the birding atlas.

Recently Neil was jailed by the Tanzanian government, claiming that Neil's birding research was a business, which is illegal under a retirement visa. When Neil went to trial, he offered his childhood birding journal as evidence of his lifelong passion for birding. The drawings and notes proved that "his birding silliness" has been going on since age five. He was released from jail to return to "retirement hobby."

When Bronwyn met Neil, he invited her to work with him and Liz on a project to catch, test and release migratory birds to look for evidence of bird flu and its spread. This activity was an example of the "One Health" discipline that has existed for many years but has recently gotten attention due to the Covid-19. We now realize that human populations are at high risk for global pandemics from diseases that originate in wild animals.

Bronwyn explained how we can anticipate the next pandemic by continuing to monitor birds. "Watch for diseases or viruses that might easily mutate in ways that allow them to impact humans. If animals weren't kept in close proximity this wouldn't be such a problem. When a wild duck with a cold infects a domesticated duck that lives alone, there is little threat, but when that duck lives with a thousand farmed ducks, and a hundred of these gets a disease, the risk changes. This increases likelihood that a mutated virus will jump from the farm animal to humans. A lone duck that is infected will die and the disease disappears."

We met up with Neil Baker again in 2019 when Charles and I invited six friends to join us for a safari in Tanzania. We wanted to organize some special birding activities for our group's avid birder, Stan Rule. Along the way to Mwagusi Safari camp, we stopped to have lunch and a birding chat with Neil.

Neil shared his excitement at discovering a new bird, the Kilombero Weaver Bird, "every birder's dream." He also shared the good news that a variety of Cisticola species he discovered in the Kilombero marshes in the 80's has been named Cisticola bakerorum in honor of his wife, Liz Baker, and will be soon featured in "Ibis".

We also had two nights at the Hondo Hondo camp in the Udzungwas, part of the Eastern Arc of African Mountainous Rain Forests formed from volcanic eruptions during ancient times. In terms of wildlife, think, "Galapagos Islands." The Udzungwas boast 1500 medicinal trees, 250 species of butterflies, and 400 species of birds. In terms of weather, think "rain" forest.

In spite of the storm clouds, the eight of us and two boatmen took a rickety boat on the Kilombera River to look for exotic birds, hippos and crocodiles. The first four birds we encountered were run-of-the-mill "Beaufort Birds". The boat slowly filled with water and our Safari mate, Alison Vernon, bailed water with a yellow plastic can. The rest of us watched the menacing sky. Thunder claps and sheets of rain ensued.

The boat guide with his preacher coat and long navigation pole, along with his partner manning the motor in back, shouted to one another about a nearby shelter. They motored toward the shore, jumped out and darted up the sandy bank. The guys took off, following the boat men. The girls scrambled through reeds with briars and then a watermelon patch with vines spreading here and there across the deep white sand. Abandoned in a Dali landscape.

Penny Rule and cousin Carol Cary heard laughter in the distance and spotted a tiny straw and thatch shelter beside which the four men huddled under two umbrellas. They were too large to fit inside the tiny hut. However, we zoomed past them, crawled inside the fisherman's hut and curled up like cats. The hut owner crouched in the corner looking a bit overwhelmed by this day's turn of events.

Too scant for standing, we squatted, knees to chin, as the rain belted the earth. One of the boatmen casually hunkered down in the door frame and lit a cigarette as he initiated a chat with his friend, the man of the hut.

Terrified of fire and overwhelmed with smoke, we scrambled out and stood in the rain with our husbands. Now we had eight muzungus (foreigners) under the two umbrellas, all soaked and laughing, until the rain subsided.

Back on the boat, we worried that the black clouds overhead and the echo of thunder drawing closer, signaled more trouble. We decided to abandon further bird watching and return to our van down river. While we were shivering and eager to get back to land, the boatman with the preacher jacket had other ideas.

He had been watching a fisherman on a small boat in the middle of the river. There was an exchange and the oarsman used his long pole to push us out toward the fisherman. I should mention that Alison was still bailing water from the boat.

There was back and forth negotiation over a tiger fish as the rain began to pelt again. Our boatman didn't like the price so turned back to shore (to our relief). Then there was more haggling. He poled the boat back out to the fisherman and paid him the negotiated price. The fisherman threw the fish into our boat. Our birding trip was foiled, and with disgruntled customers, the boat guide anticipated that his tips would be far less than on a good birding day. At least his wife would be happy with the fish.

I went to see Stan Rule the other day to get his advice for a beginning birder. At the start of our conversation, I asked him what he remembered about our birdwatching excursion in Tanzania. Stan grinned and said, "I remember the joy of us running through the brush and coming to this hut and they were so welcoming for us to be there. We were so far from home and welcomed into this hut in the midst of the rain. It was pleasant, the warmth."

That is not how I remembered the trip, but then again, Stan is saintlier than I. Stan has applied his immense patience (adolescent pediatrician) and a heart filled with love for all living things, to his bird watching.

I told Stan about my goal to identify my backyard birds. I asked Stan how he got started in birding and what advice he could offer. This is what he said:

"People think of me as a birder, but I only think of myself as someone who loves to look at birds. I am at a high level of enjoyment but not at the proficiency to identify things moving fast. I started photographing birds that I don't recognize and then bringing them home to study due to my vision and hearing problems."

Differences include male and female, seasons of the year, or molting. He gave an example of the challenges to distinguish a common bird. " One day I saw this fabulous small white bird standing near a Little Blue Heron in the marsh. I thought I had discovered a new bird, but when I photographed it and used my apps for identification, I found that this was the first year of the Little Blue heron; its youngster is white.

Adult and juvenile Little Blue Heron

Stan advises to look for birds when light is breaking. Birds start singing to connect with other birds in their species. Also, they don't move a lot, as they are sitting in the sun to warm up.

"Birding brings you close to nature and makes you think about the environment. Birding is thrilling because you don't know what you will see." He gave an example of a miraculous sighting, eight Piping Plovers, all on Rachel Carson Reserve in one morning. The Piping Plover is an endangered bird, with an estimated 3,000 remaining in the world. He says, "Watching changes in your local birding population brings the birder to a state of awe and reverence, a desire to do something to protect these little wonders."

Stan sees benefits to creating bird habitats in our community. "Plant your yard to attract birds. Audubon society offers suggestions for bird friendly and native plants. Be thoughtful about the benefits to birds, something native that attracts birds. Also, plants that fruit in different seasons will attract birds over longer seasons."

Stan recommends two phone apps for beginning bird watching:

1. Merlin Bird ID by Cornell Lab

2. Audubon Bird Guide

To use the apps for identification, look closely at the bird, with binoculars, a scope, or digital camera. If you are "dirty birding", watching birds that move fast, you won't have time for the equipment, only your eyes. Fast moving birds do not afford time for the birder to look back and forth between a bird book or app and the bird on the limb or in flight.

Note their color, the bill, any markings, the wings, size and activity before turning to the app. Both of the apps help you identify the bird by checking boxes related to these characteristics. If there are two birds together but do not look alike, then they are probably male and female, or adult and juvenile. The apps will display possible birds based on your GPS location and the data you inserted.

These apps also allow identification by sound, but this should be used minimally, because the sound can distract birds and put them in danger. Since talking to Stan, I realized there is a chorus of bird sounds I can hear from my front porch in the late afternoon. Perhaps that is why I enjoy sitting there, but was unaware. They provided a musical backdrop that I never really heard. Two days ago I noted there were six different bird calls and songs I could hear from my porch swing. Between songs at my outdoor Zumba class I can now hear birds. This birding pursuit is exercising my senses.

When Stan isn't watching birds, he carves them. He got started carving after a conversation with table-mates at a community dinner celebrating local and organic fresh foods. At their table for eight, three of the men were bird carvers. They invited Stan to join them the next morning. They handed Stan some tools and took him through the basic steps of carving a Coot. The men carved and talked about birds and life. As he carved, Stan, felt an affinity to his grandfather who was a master carver of furniture reliefs. Stan was hooked! Stan now carves 50-60 birds per year.

We live in a community of decorative bird carvers. Duck decoy carving has a long tradition from Beaufort to Cedar Island. That's what the boat builders did to pass cold winter days, not only to lure ducks to put food on the table, but for the fun or "vengeance" of competitive carving and painting. A visit to the Core Sound Waterfowl Museum on Harker's island is a magical foray into their world. They hold an annual Decoy Festival and in 2019, Stan was the featured carver.

I am now a novice "birder", equipped with my simplified bird book and all these great tools and insights from naturalists. I am determined to identify all my "backyard birds" and also the sea and marsh birds a block from my house.

Charles said "backyard means backyard," robins not pelicans, until I pointed to the white Ibis strutting down our front sidewalk. I rest my case regarding definitions of "backyard" and am even thinking about birds in the NC mountains, my state, my backyard, so to speak.

Finally, I return to my opening question: What's so great about birding? I'll take Stan's answer.

"Birding is not all about birding. You learn how little we are and how wonderful are the other creatures of the world. It balances our perspective on where we fit."

Photo Credits:

Dan Dye shared two photos of male painted buntings in our back garden.

Neil Baker supplied photos of his family and the Cisticola Bakerorum photographed by Pet Holman.

Stan Rule shared photos of the female bunting, the Little Blue Herons, the cardinal, the dove and his own woodcarvings.

Charles Llewellyn photographed the white ibis on the front walk. All other photos from the author, Deborah Llewellyn.

Loved this. Joyful and took me back to Tanzania.

All great writings...thank you opening my eyes once again!