The Middle Passage –A Heartbreaking Journey from Ghana to Beaufort, NC

- Deborah Llewellyn

- Feb 6, 2022

- 24 min read

Updated: Feb 8, 2022

On October 15, 2021, I stood where enslaved Africans took their first steps on colonial American soil, at what is now Topsail Park in Beaufort, NC. I have also stood where captured Africans took final steps from their homeland in Ghana, West Africa. To stand like bookends at these points of departure and arrival, is to be filled with moaning ghosts.

In this blog I will talk about how living in Africa increased my inteest to learn about the slave trade and African American history. I will also consider what the Middle Passage project in Beaufort can mean to our town.

Beaufort, NC was involved in the Trans-Atlantic human trade and is a documented Middle Passage arrival site. Beaufort was a minor point of entry compared to Charleston, SC, which received half the 12.5 million enslaved Africans imported to the colonies, but every man, woman, and child sold in Beaufort, weighs just as heavily on our town's collective conscience.

The number of arrivals from Africa to Beaufort's port is currently unknown, but there are public records such as this one that indicates 179 Africans arrived from Africa to the Beaufort docks between October 1763 and 1764.

In addition to direct import from Africa, other enslaved Africans came to Beaufort indirectly from other ports of entry along the eastern coast and from the Caribbean through New Orleans. They were purchased second hand from other slave owners in the colonies. These African men and women played a significant role in the development of Beaufort's infrastructure and maritime industries. They could have done so as paid immigrants rather than enslaved property.

On that October day, I was attending a Middle Passage Ceremony and Port Marker Dedication in Beaufort, now named as a Site of Memory, by the UNESCO Slave Route Project.

The Beaufort project was a grassroots effort, organized, designed, funded and installed by members of the community, and led by Heather Walker, Director, Eastern Carolina Foundation for Equity and Equality (www.facebook.com/ecfee). The work was done in conjunction with The Middle Passages Ceremonies and Port Marker project and endorsed by the National Park Service.

It was a moving ceremony that provoked personal memories of living in Africa, and a desire to know more about the contributions of enslaved and freed Africans to the development of my hometown, as well as their struggles.

Ghana was our third overseas post as a U.S. Foreign Service family. I flew to Ghana in late summer of 1993 with my children, Bronwyn and Chas, to an airport waiting area filled with a sea of Black people. I was now a racial minority, intending to learn from the opportunity.

Our plane was filled with a diaspora of Ghanaians returning home from lives abroad, a sprinkling of whites, and probably a few American Blacks on a "roots" trip. During the flight, the passengers talked over their seats and up and down the aisle in such a familiar and friendly manner that I assumed they were relatives or friends. I came to understand over time that the travelers likely did not know each other; they simply bubbled over with beatific friendliness so common to the broader Ghanaian culture.

As we approached landing, the Ghanaians cheered and clapped. This was a first for me. To see so much love and pride of homeland that arrivals are met with celebration. I'd be surprised to see that on an international flight landing in La Guardia or Atlanta, but it is common on planes landing in Ghana from abroad.

When my children and I walked through arrivals searching for my husband, we were greeted by so many people. "Welcome," they said over and over with beaming smiles for my children and me, passing us along the way, through thick crowds and the pungent smell of palm oil. I was so startled by the friendliness that I wrongly assumed that these people were from my husband's office, somehow with permission to enter restricted areas where my husband was not. We met up with Charles and worked our way to the sandy car lot lit by the moon and stars and lined with tall palms swishing in the sea breeze. We were not only blanketed in tropical heat but also by more warm welcomes from taxi drivers, vendors, just anyone at all.

As a child, I could not understand America's institutional and socially embedded racism, nor the covert racism based on false science that African Americans are biologically inferior, the 'big lie' being used to rationalize cruel, un-Christian behavior of some whites toward Blacks. Going to Ghana allowed me to see how Blacks lived without racism, in a country that they ran, and ran well.

It was a joy to live in Ghana and interact with African professionals, government officials, neighbors and business people I saw regularly such as tailors, market vendors, and my skilled and friendly hairdresser, who gave head massages as part of the shampoo. The children were well cared for and such a delight to meet

We were granted a special privilege to have three delightful Ghanaians, Eric, Helen and Albert, work in our house and help us navigate all things Ghana. Eric made to-die-for cinnamon rolls and will always hold a special place of joy in Chas's heart for playing roller-blade hockey on our long hallway and "don't touch the floor "tag on the living room furniture, when Charles and I were not at home.

Helen, both literally and figuratively, saved my life (but that's another story) and had an eye for finding absolutely essential lost Lego pieces.

Albert, a miraculous gardener/driver helped keep snakes out of the house, my mom from being arrested when she became too curious about a restricted mental institution and bargained best prices for Charles's mom at the crafts market.

Through Albert's safe escort on pot-holed roads to the stables, Bronwyn was able to seek adventure in the African bush on her retired polo pony, Butterfly (which is also another story). Armed with a butterfly net, Albert caught a jar of moths for our pet chameleon's dinner every afternoon. He much earned the car we gave him to start his own taxi business after our departure.

These kind, clever and personable individuals gave us the up-close snapshot of the heart of Ghana. Sometimes I miss them so much I want to weep.

As a society, Ghanaians tend to have a quick wit, great sense of humor, and a high level of curiosity, asking sharp questions that get to the core of the matter. Generally speaking, they are sophisticated and self-confident. Those who come from abroad to work in Ghana quickly learn that Ghanaians do not suffer fools. You better know your stuff and appreciate that you are on absolutely equal grounds in terms of intelligence, education, and insights. You must be willing to listen and learn.

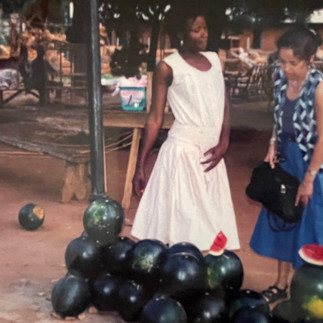

Ghanaians walk with grace and statuesque postures. No matter how poor, they take care about appearance, women wearing matching head scarves and simple cotton shifts and fisherman wearing colorful wraps. Male laborers dress in spiffy "safari clothes" on weekdays and colorful printed shirts for office attire and weekends.

For dressing up, they keep an army of tailors busy working magic with hand block-printed and dyed fabrics. Women judge other women's dress by the layers of cloth used to form puffy sleeves and intricate embroidered cutouts on the bodice, as well as their beads.

For funerals, a family buys bolts of printed cloth, usually in black-and-red patterns, sometimes in black-and-white, or red-and-white. Everyone in the procession behind the casket wears clothing articles from the same fabric. A funeral procession takes the breath of onlookers.

I frequently wore basic black dresses or suits and bright red beads to my office. One day, the designated news bearer pulled me aside and told me that the way I dressed made my office-mates feel awkward, that when I dress in black and red, it brings funerals to mind. This lesson taught me that foreigners must be acutely aware that what is normal for one culture is not for another. That any of the things I think I learned about Ghana may be laced with inaccuracies, and limited vision to appreciate other ways of looking at the world. This should be taken into consideration as I share my experiences living in Ghana.

Ghanaians value education and students follow a stringent curriculum. Our seventh-grade daughter, Bronwyn, was not challenged in the American International School, so we visited the prestigious Ghanaian International School (GIS) not far from our house.

The campus spread across a large parcel of land and enrolled over 1,000 pupils, some who came from neighboring countries and boarded at the school. The director showed us around, asked questions, and then told us that she would consider enrolling Bronwyn but we should know that most American students did not do well there, lacking the discipline to manage the rigorous curriculum, the amount of memorization required, and the rote exams demanding recall of facts.

The headmaster's cleverly posed "challenge," made Bronwyn want to enroll and prove her wrong. Bronwyn was forced on her toes to manage seven classes with seven teachers, following an African/British IB curriculum. It was the first time she had been academically challenged, and we were proud of her achievements. In the past we had worried that Bronwyn seemed a bit lazy, academically, in spite of her brilliant mind. Her grandfather, a psychiatrist, told us she lacked challenge. He was right, as in so many things.

To get to school, Bronwyn rode her bicycle through a bit of jungle, along a ravine, passing through the porches of a hairdresser's salon, a bar, and a bead dealer. The jungle path was a convenient shortcut that kept her from biking on a busy street. We never worried about her safety, even when she biked through the bar. We learned very quickly that Ghanaians have high morals, and practice Christianity in their daily lives, not just on Sunday. We knew that the hairdresser, the bartender and patrons would greet her and watch over her as she passed by two times a day.

In rural areas I saw how children worked hard for an education. When I asked them how far they walked to school, most walked an hour or more, and spent the day there without any food or water until they returned home in the afternoon. And still they came.

Just as in America, African governments do not invest in high quality, equitable education for the poor, because education is power. I was able to see how brilliant the minds and skills of African adults who had been raised in poverty but given opportunity to study.

Still, I was amazed when the headmaster at a rural school I was visiting in South Africa, asked if I had time for the children to perform. About fifty children with violins (donated from an American classical musician) played a classical piece followed by spirituals in which fifty more children sang in glorious harmonies, all standing in bare feet in the shade of the classroom building. How I wish I had a photo of that experience.

Across Africa, I enjoyed exceptional musical aptitude in acapella choirs, skilled drummers, and dancers telling stories.

A Krobos chief had a city house across from our house. He frequently held ceremonies and celebrations, always with the best drumming groups from his tribe. We enjoyed vicariously from our front screened porch, discovering that drums can make a multitude of pleasing sounds and harmonies, and even when they played for hours we never tired of this beautiful music.

Talking drums can produce enough distinct sounds to cover the alphabet, so to produce words and messages, an old form communication, long before cell phones. Once my office planned to visit a school but date and time were changed at short notice. I was astonished when we arrived at the school to find all the parents and children. "How did you know?" I asked. A parent laughed and replied, "The talking drum told us when to come, what for, and what time. We can hear it from our houses in the distance."

At the Middle Passages ceremony, several speakers emphasized the importance of forgiveness. I had often wondered where the spiritual energy of African Americans in the American south comes from, to believe in a better tomorrow in spite of the wrongs that have been done to them. In Africa I could see the roots of Martin Luther King, John Lewis and James Clyburn's deep spiritualism, kindness, and commitment to non-violent protests. As I flew from country to country, I found humor in the numbers of American missionaries flying into the continent to save souls, like bringing coals to New Castle, I concluded.

I grew to admire the skilled artisanship and creativity that rendered ordinary functional objects into things of beauty. Besides high quality textiles and design, Ghanaians produce numerous other art forms such as metal work, wood carving, drum making, painting, and fine basketry. In Ghana, one can purchase a casket that makes a statement about your livelihood and aspirations, such as a Mercedes, a jet plane, fishing boats, and animals. In these photos, Ruth Bowen decides between lion or elephant, Grace Llewellyn picks the bird, and I am feeling like a mother hen.

There are also skilled oil painters, who fetch a high price on the international market for their paintings. My favorite painting from Ghana depicts the wife of Ablade Glover, one of the nation's top painters. We spent many enjoyable afternoons visiting the painting galleries along the beach interspersed with colorful casket shops. Saturday was not complete without a trip to the vegetable, crafts and antiquities market, and some local cuisine for lunch.

I have been known to judge a country by its food. Our first Saturday lunch at a popular restaurant, Country Kitchen, was fufu (dough-like food made from pounded cassava), topped with groundnut stew, a delicious concoction of ground peanuts, eggplant, tomatoes, okra, garlic, onions, and chilies simmered for hours to create a thick sauce of melded flavors. When you can visit a rural village and be fed a dozen side dishes of vegetables, it indicates something about intellect – a need for complex flavors and the capacity to grow and cook such an array of healthy foods. Ghana ranks high in best food countries and has had an impressive influence on the cuisine of the American south.

Ghana has a long history of well-organized kingdoms, such as Ashanti and Akan nations, that developed expertise to produce museum quality functional art. For example, the calibrated brass weights to measure gold and gold dust exist in dozens of tiny animal figures. Our children collected replicas of these. Chief's stools and linguist staffs with changeable tops to represent the purpose of the meeting were other examples.

Cape Coast was our first excursion out of Accra, the capital. Our colleagues suggested that we visit the castles and forts that dot the Ghanaian Coast, the largest being in Cape Coast.

The oldest, Elmina Castle, was constructed by the Portuguese in the 15th century. Between 1400's to 1800's, approximately forty forts were built by a half dozen European countries along the coast of Ghana, with the Dutch West Indies Company having the greatest presence.

Upon arrival to Cape Coast, we set out to explore the castle, posing for a family photo. Ghana was known to Europeans as the Gold Coast. The coastal forts initially served as fortified trading posts for Europeans to trade manufactured commodities for gold from tribal kings. The forts offered protection from other foreign traders and threats from the African population.

Only upon entering the Cape Coast castle and reading placards did we realize the most notable purpose for the limestone fortresses that dot the coast. While initially built for commodity trading, the castles became central to the slave trade. Prior to our arrival in 1993, UNESCO, had begun work to establish museum exhibits in the most prominent forts along the coast in order to explain the African slave trade to visitors. Some of the local assistants hired to help with the exhibits became informed tour guides. What we thought would be a fun day tromping through parapets turned out to be a somber day with a harsh awakening.

We hired one of the tour guides who led us to the dungeons where captured men and women were separated in dark and poorly ventilated holding rooms. Narrow openings near the ceiling allowed some light and air, but the stench must have been overpowering as there were no toilet facilities. Women were brought out to the courtyard in the afternoons, where the castle agents could peer at them from the balconies above, choosing which one he wished to rape that night. Our guide told us what happened when the prisoners fought back. Any revolt was harshly disciplined. Men were sent to a dark, windowless, confinement cell for the condemned and were starved to death, while women were beaten and chained to cannon balls in the courtyard.

When the slave quota was met, a European ship arrived. Enslaved men and women were forced through the 'door of no return' and dropped onto the ship's deck, where they briefly saw their family members before being shackled in separate compartments of the ship. My family stood in silence on this limestone rampart that jutted out to the sea and imagined their beaten, starved bodies and their terror at what had happened to them and what lay ahead.

Before visiting Cape Coast, we had wondered why Ghanaians did not take advantage of the vast coastlines for high market home sites, as we do in America. Even tourist hotels were built perpendicular to the ocean, with no views from the porches or windows out to the ocean. The response we got was this, "Africans turn their back to the sea." We finally knew what that meant.

Modern day West Africans have a long memory about the 'First Passage' in the slave trade, where thousands of free individuals were kidnapped, shackled and marched from the interior to the sea, along paths littered with human bones. Who were the captors? Africans would like to attribute this travesty to European slave traders. While assuaging some guilt, this does not stand up to historical record.

When I looked into the question of African participation in the slave trade I learned that African Kings, Warlords and private kidnappers captured and sold slaves. Although Europeans provided the market for slaves, they rarely entered the interior of Africa due to fear of disease and fierce African resistance (Wikipedia).

In the early days of fort construction and commodities trading (1400's-1500's), historical archives show that Europeans initially ambushed and captured Africans from fishing villages along the coast and took them back to Europe to sell, along with the commodities they traded for in Ghana, such as gold, mahogany, bronze sculptures and locally produced goods.

In exchange, Africans received guns and ammunition, clothing, blankets, spices, silk, sugar, cowrie shells, beads and other commercially produced goods.

As the demand for slaves from the Americas increased, humans became the major commodity in trading between Europeans and Africans, with Africans supplying the slaves. Those historians purporting this view say that Europeans could not have captured the estimated 12.5 million slaves purchased for trade in the Americas. Africans, themselves, caught and sold other Africans. That relieves none of us from the guilt for what happened. It speaks to our shared responsibility to face our dark past, to realize slavery's effects on our social fabric, and to seek reconciliation.

"While there had been a slave trade within Africa prior to the arrival of Europeans, the massive European demand for slaves and the introduction of firearms radically transformed West and Central African society. A growing number of Africans were enslaved (by Africans) for petty debts, minor criminal offenses and through unprovoked raids on unprotected villages. An increasing number of religious and tribal wars broke out in West Africa with the goal of capturing entire villages of slaves, made possible through the use of European weapons" (www.digitalhistory.uk.edu).

In most cases, rulers or merchants did not think of supplying slaves as an act of selling their own subjects, but people they regarded as alien. "We must remember that Africans did not think of themselves as Africans, but as members of separate nations." (Wikipedia)

The African captives were bound together at the neck and marched barefoot hundreds of miles to the Atlantic Ocean. They typically suffered death rates of 20 percent or more while being marched overland. The captives who survived the forced march to the sea, referred to as the "First Passage," were then examined by European slave traders at the forts.

In one document, a slave trader explained his criteria for purchasing Africans from the tribal chiefs: "The Countenance and Stature, a good set of teeth, pliancy in the Limbs and Joints, and being free of Venereal Taint, are the things inspected and governs our choice in buying." Those purchased were branded with hot irons, assigned numbers, and forced aboard ships; the others were simply abandoned (Wikipedia).

The Middle Passage was the second stage of the slave trade where captives were taken by ship from West Africa to the Americas, suffering horrific conditions. The close quarters and intentional division of pre-established African communities motivated enslaved Africans to forge bonds of kinship, which then created forced transatlantic communities. An estimated 15% of the Africans died at sea. The number of deaths directly attributed to the institution of slavery from 1500 to 1900 suggests up to four million. (Source: Smithsonian Museum of African American History and Culture).

It is hard to fathom the emotional and physical pain of enslaved Africans endured during the Middle Passage and upon arrival in the "new world." Imagine the lives of men, women and children under chattel slavery who remembered their African homeland, and for their descendants who were frequently torn from their African American family and sold to distant plantations, where they not only lost loved ones but also the stories of their origin.

The post traumatic effects of slavery endure in social, psychological, educational, economic and health problems endemic to African American culture today.

The slave trade was not only a horrific experience for the enslaved, but it also had negative effects for everyone involved. Over time, slavery devastated west African nations through loss of human capital, increase of hostilities and warfare fueled by arms, and dependency on western goods which dried up with abolishment of slavery in the 1860's.

On a smaller scale, consider how it debased the European captains and sailors, who viewed the work as a living nightmare, but who none the less, carried out the cruel treatment of the passengers. No one willingly signed on to this job; most of the sailors were debtors or convicts, forced to do the work. The captains were driven by greed. The slave trade legacy provides the underpinning of culture wars that still threaten the foundation of our democracy in America.

The slave trade legacy is also present in West Africa today. Many African-Americans who visit West Africa are unsettled to find that Africans treat them -- even refer to them -- the same way as white tourists. The term "obruni," or "white foreigner," is applied regardless of skin color. I had observed Ghanaian scorn of Black Americans, who return to the "homeland" with an attitude of elitism. The Americans often behave as if they are superior to their Ghanaian hosts.

Ghanaians generally have a distaste for these tourists. I asked why, and an outspoken colleague delivered this chilling remark, "They think they are special because they are Americans but they were once our slaves."

Once I did some research on African participation in the slave trade, I came to understand the comment and to realize that classism or "caste" is deep-seated in both Africa and America. The entrenched prejudice of some Ghanaians against American Blacks and many American whites against Blacks persists 150 years after the slave trade ended.

Although Ghanaian economy benefits from American "roots trips", the government has been forced to launch propaganda campaigns to Ghanaians urging them to be nicer to these Black American tourists. American historians have asked society to consider the far-reaching effects of racism on the institutions of our society (Critical Race theory). The lasting truth from the history of chattel slavery is that it reveals the darkest aspect of human nature, the ability to create a mind-set that some humans are worth less than others in order to justify inferior or in-humane treatment.

To realize that Africans were as culpable in this horror as were the Europeans, is a call to examine the long history of caste in all cultures, which I have written about in a previous blog. Caste derives from a belief that some people hold higher status based on contrived rules, and that all people are not created equal. The ability of humans to shamelessly enslave fellow humans and call them "other" has a long reach from the past to contemporary societies.

While social consciousness has shifted and laws were created to abolish chattel slavery, it still exists in other forms. Just look to the American prison economy as evidence. Consider neighborhood demographics and cost of car insurance, who holds certain jobs, and racial profiling by highway patrolmen. Listen to what every African American parent must teach their children to help them survive in a white dominated, racist society. Look to the backlash against teaching Critical Race Theory, which examines embedded racism in our culture and institutions. Consider the global trade of child and human trafficking which I wrote about in my novel, The Drawing Game.

Shortly after attending the Middle Passage ceremony in Beaufort, I visited the Smithsonian Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) with my husband and daughter. The museum offers bountiful resources for understanding African American history, both struggles and contributions.

The tour appropriately starts in the dark bowels of the museum's sub-level. This exhibition explores the complex story of slavery and freedom which rests at the core of our nation’s shared history. The exhibition begins in 15th century Africa and Europe, extends up through the founding of the United States, and concludes with the nation’s transformation during the Civil War and Reconstruction.

NMAAHC use "powerful objects and first person accounts" to raise awareness about both free and enslaved African Americans’ contributions to the making of America. The museum exhibits also explore the economic and political legacies of the making of modern slavery. The exhibition emphasizes that American slavery and American freedom is a shared history and that the actions of ordinary men and women, demanding freedom, transformed our nation (NMAAHC website)."

Currently there is a an online video tour in the newly developed "searchable museum" on the subject of "Slavery and Freedom: 1400-1877 exhibit with Museum specialist and co-curator Mary Elliot at this site: https://www.c-span.org/video/?424004-1/slavery-freedom-exhibit.

My visit to the Smithsonian and on-line research enhanced my appreciation for the Middle Passage Port Marker Dedication that I attended in October 2021. I now realize how much this occasion must have meant to my neighbors of African descent, as well as its importance in my own journey to understand and promote equity.

I met with principal organizer, Heather Walker, to get some background on the event. I asked her what it meant to her and Beaufort's Black community, and inquired about her future hopes as Director of Operations for the Eastern Carolina Foundation for Equity and Equality. I knew that Heather would be a good resource to learn about the role of African Americans in Beaufort's development.

Heather admitted that it was initially challenging to get the hands-on help needed to produce this somber, yet celebratory event, especially from the eight children, dressed in Sunday best. But once the significance of it became evident, there was a groundswell of pride from the children and adults. The Middle Passage committee included twenty-eight distinguished members of Beaufort's African American community, including Commissioner Sharon Harker (elected Mayor in November 2021), Bishop Donald Crooms, elder statesman Rosina Henderson, and a rising leader, Tyesha Teel, as well as several children and teens – Anthony Walker, K'yrah Reels, Ivory Crooms, Reality Oliver, Sabre Tepetate, La'tecyia Johnson, Steven Walker, and Sarah Walker.

Guest speaker, Ann Cobb, Executive Director of the Middle Passages Ceremonies and Port Marker Project, Inc., (pictured with hat) came from Baltimore but has important links to African American history in North Carolina. Her father, Reverend Dr. Charles East Cobb, was a defender of the Wilmington 10.

The "Wilmington 10" refers to ten civil rights activists who were falsely convicted and incarcerated for nearly a decade following a 1971 riot in Wilmington, North Carolina, over school desegregation. Reverend Dr. Cobbs and the Congregational Church in Wilmington raised $750,000 for their bail and other legal fees. Here is a link for more information: https://www.nytimes.com/1999/01/04/nyregion/charles-earl-cobb-82-minister-and-advocate-for-civil-rights.html

Another speaker, B.G. Horvat from the National Park Service, talked about his own reckoning with the history of slavery in Beaufort and the importance of African American enterprise to the town of Beaufort. He pledged the Park Service office's commitment to highlight that journey through a permanent display in downtown Beaufort at the visitor's center. The National Park service has announced a partnership with ECFEE to create an African American Heritage Tour throughout Eastern North Carolina.

I asked Heather what was important to know about the commemoration of Topsail Park Site of Memory. She said, "On a personal level I want to educate my children of their heritage, to know that they came from greatness and that it was taken from them. I want them to know that Beaufort's African American community has a long history of strength and resilience since arrival here. It is important that the town, that all citizens understand that this is a sacred place, and to treat it with reverence."

Heather shared stories about the strength and resilience of the Black community. "Every personal success came at great cost from overcoming hurdles. Whatever is accomplished must be appreciated not just for what it is but what had to be overcome. People think that Black success is an exception, but it is the standard. The park dedication gives the Black community a renewed sense of pride in themselves, and their heritage."

Prior to the UNESCO designation of Topsail Park as a Middle Passage port of entry for African slaves, the Beaufort Garden Club committed to landscaping the once derelict park and maintaining the garden. The Club designed and installed the attractive plants, walkway and seating area. The club also commissioned the production of a statue commemorating the Menhaden fishing industry to be placed in the park. The Beaufort Garden Club president stated, "Topsail Park is a place of remembrance, and the Beaufort Garden Club’s hope is that public art will further compliment this very important space on Beaufort’s historic waterfront."

While the landscape contributes to the beauty of the Port Marker, the statue's significance might be considered an irony in the park's designation as a site of memory for enslaved people who survived the Middle Passage and contributed to the town's development. The Menhaden industry was important to Beaufort's development, but its success depended on both the maritime skills and capacity for grueling work found in Beaufort's African American community. To bring meaning to apparent contradiction, a permanent marker explaining this history would be beneficial and appropriate at the Site of Memory.

The Menhaden industry was built on exploitation of Black labor, but it also contributed to their freedom. This history is documented in a book by David Cecelski, The Waterman's Song, Slavery and Freedom in Maritime North Carolina (2001), as well as other books and academic papers he has written on the subject. Skilled in all aspects of maritime work, African Americans were able to assume unusual power, even to form unions in the menhaden plants, due to their capacity for hard work that local whites would not do, and their indispensable prowess over fishing, boat-building and sailing in the complex coastal waterways.

To learn more about Beaufort's African American history, check out the Eastern Carolina Foundation for Equity and Equality's newsletter (Info@NCECFEE.org) or contact Director Heather Walker for a tour of Beaufort's African Heritage Trail.

Historical trails help to show a pattern of events. For example, numerous freed Africans attained wealth and social status, living in fine homes on or near Front Street before a designated "colored section" was developed north of Broad Street. We can learn about education institutions in Beaufort that provided opportunities for the Black population to gain literacy after the Emancipation Proclamation and stories behind the burning of these schools and other Black institutions in Beaufort, the acquisition of land by free blacks and the taking of their property as land became desirable to white developers.

An African American history trail gives opportunity to learn surprising facts. For example, Beaufort protected large numbers of slaves and free men and women in its Union Town as the civil war came to a close. But also important to know that no elections were held in Beaufort from 1898-1901 for fear of "Negro Rule" during a time that Africans far outnumbered whites in Beaufort.

The Eastern Carolina Foundation for Equity and Equality is creating a pop-up African American Heritage exhibit in February 2022; and other exhibits each August in conjunction with United Nations International Day of Remembrance for the Slave Trade and its Abolition.

The non-profit Foundation welcomes volunteers to help with the newsletter, collection of oral histories, and the African American History tour.

I loved Heather's stories and invite readers to do their own research into Beaufort's African American history. A great starting point for me was a Library of Congress document that Heather shared through a link [https://1drv.ms/b/s!Ag2ZWH-EdcZ4pj7Z7zz2aUrrz-4R]. The document was written by Reverend Horace James, the Superintendent of Negro Affairs, and provides specific data on the contributions of freedmen in coastal North Carolina, including Beaufort during the year 1864. This document lays out the hard data on the productivity and accomplishments of freedmen in Beaufort and other coastal towns during the year 1864.

One can also turn to a new book, Beaufort North Carolina, African American History and Architecture, by Peter Sandbeck and Mary Warshaw, published in 2021, locally available in Beaufort downtown shops and online. Peter Sandbleck, Architectural Historian and Preservationist consultant compiled some basic information readily available in public records and is a place to start.

This book left me hanging. I wanted historical time lines and the truth of events, oral histories and first person documents, a book that was written in consultation with Black leaders in our community. A little more heart, a little more soul-searching in the truth-telling of Beaufort's black history.

In Jamelle Bouie's New York Time's Opinion Piece (January 28, 2022), "We Still Can't See American Slavery for What It Was," he discussed a ground breaking research tool for scholars of slavery and the slave trade. The SlaveVoyages database (https://www.slavevoyages.org) is accessible to the public, and represents ten years of work to quantify the slave trade back to the early 1800's. The principal investigators are continuing the work to gather ship's manifests, the ports of embarkation and debarkation and the contents of the ships including names.

American slave owners did not use or care about the actual names of their slaves, and over time enslaved people adopted the owners surname as their own. That enables African Americans to track down the plantations or individuals who owned their ancestors, and then to find out where the slave owner obtained his enslaved men and women. The SlaveVoyages data base goes further. By using the embarkation manifests of slave traders who were required to document cargo for federal authorities, scholars are finding out the actual African surnames of those enslaved, which can be a major breakthrough for all of us with African blood to trace our ancestry. We can draw connections and get closer to our heritage.

By giving a name to these individuals we know not just the size and scale of the slave trade but also a more intimate story about once free people who were forced into this condition. In the NYT's essay cited above, Jamelle Bouie, wrote that when history provides numbers and not human stories, it leaves us with a "numbness of empathy, a numbness to human interconnection.”

In my study, I came across an interesting thought but can no longer identify its source. It is this: "We may not have many statues of the enslaved — we may not have anywhere near enough letters and portraits and personal records for the millions who lived and died in bondage — but they were living, breathing individuals nonetheless, as real to the world as the men and women we put on pedestals.

My experiences living in two African countries and working in twelve others, changed me. I grew to respect Africans as my equals, to care about their lives, and develop deep friendships and human connections.

The UNESCO Ports Project is an opportunity to move in that direction as a town, to reckon with the acts of violence by some and the humanity and bravery of others, and ultimately find the ties that bind. As much as possible we need real names and authentic stories that bring Beaufort's African American history to light and make us care enough to build a more equitable community. Otherwise, we can dedicate a park, brush off our hands and declare the work done, or through this project, we can internalize the meaning of Jamelle Bouiee's closing words in his NYT's essay: "It's possible to disturb a grave, without touching the soil."

I recently re-examined the program given to me at the Port Marker Dedication. The back of the program displays the Sankofa symbol of the Akan tribe in Ghana meaning, "You must know your past to know where you are going."

This blog gave me opportunity to delve into the heartbreaking story of the Middle Passage and to learn some of Beaufort's fascinating African American history. I encourage others to take this journey, as well, and by uncovering our dark legacy, we can also find stories of resilience and redemption.

The study of African American history is a necessary journey for moving from a caste view of society toward equity and equality. Seeing the likenesses that bring us together and our differences which make us delightfully unique, is the essential humanity for building a great place to live and a stronger, more inclusive family called Beaufort, NC.

Written by Deborah Llewellyn, Beaufort, NC

https://deborah-llewellyn.com/blog

Credits and Links:

Photos: All photos taken by the author, Deborah Llewellyn, or her mother, Ruth Bowen, when she visited our home in Ghana in 1994, with the exception of the beautiful BBC photo of the Cape Coast Castle taken from water view; the Ghana airways stock photos; and Ghana International School website photos.

Contact Heather Walker, Operations Director, Eastern Carolina Foundation for Equity and Equality at www.facebook.com/ecfee. If someone wants to volunteer, they can email Heather at: info@ecfee.org or equalityforenc@gmail.com, or click the "Contact Us" button on the website.

Preserving black history in Beaufort blog

UNESCO documentary on the Forts and Castles on the Ghanaian Coast: https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=UNESCO+documentary+on+the+Forts+and+Castles+on+the+Ghanaian+Coast%3A

TED Talk on Middle Passage Atlantic slave trade:

"Slavery and Freedom video, Smithsonian Museum: https://www.c-span.org/video/?424004-1/slavery-freedom-exhibit

Beaufort Middle Passage Data can be found at https://www.middlepassageproject.org/2020/06/03/african-presence-in-north-carolina/

Photos and videos of Ghanaian Slave Castles:

https://theculturetrip.com/africa/ghana/articles/ghana-s-slave-castles-the-shocking-story-of-the-

UNESCO documentary on the Forts and Castles on the Ghanaian Coast: https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=UNESCO+documentary+on+the+Forts+and+Castles+on+the+Ghanaian+Coast%3A

African participation in the slave trade

Middle Passage Overview and Sources of Information (Wikipedia)

Implications of the slave trade for African societies:

Slave trade history:

https://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/history-of-slavery/west-africa

National Park Service – UNESCO Site of Memory Project and Slavery trade data

Comments