Bangladeshi street dogs are territorial. One mutt, or a small pack of strays, keeps to one block in a neighborhood. They spend most of their time splayed out on the sidewalk, unperturbed by footsteps, comfortable in their own fur and sense of place. For food, the lean creatures manage to scrape by on day old bread that tea vendors toss to them and the last few morsels of rice and lentils scraped from the tin bowls of guards who mind the gates along the block. Bangladeshi’s are kindly people.

The street dogs also eat from the kitchen wastes piled on designated corners in the early mornings before the garbage pickers arrive to recycle every scrap of trash. Each item has value. Cardboard, paper, plastic bottles, tin cans are sold to factories that produce recycled products. Food wastes are redistributed to feed goats.

Alert to times that the guards eat their midday meal, the dogs hop to attention. The remainder of the day, they laze around unless they sniff a new dog invading their territory. Expats with dogs on leashes quickly learn how to befriend the street dogs and avoid dog fights by tossing dog food pellets to the strays. Having received the dues, the street dog barely raises an eye, having given permission for the fancy dogs to pass.

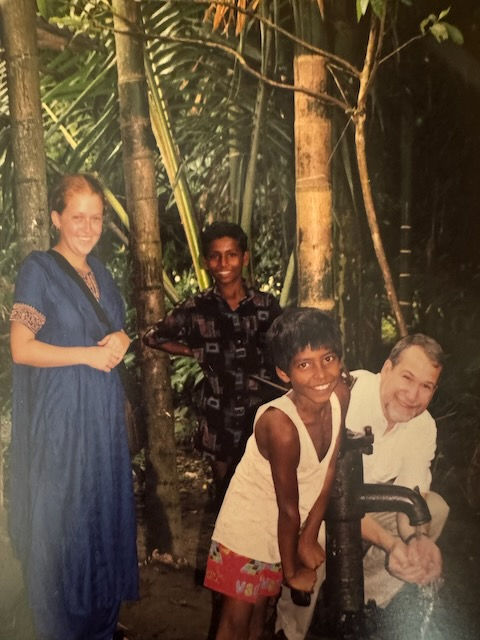

My husband, Charles, and I recently returned to Bangladesh to visit our daughter who works for USAID as the Environment Office Team Leader. As a family, we lived in Bangladesh from 2000-2005 while my husband was posted to USAID as Health Team Leader.

Photo: Bronwyn assisting her dad with public health work in 2001.

I was eager to observe improvements in poverty reduction and development, and there were many. In 1971, at the nation’s birth, Bangladesh was designated as one of the poorest countries. It reached lower-middle income status in 2015 and is now on track to graduate from the UN’s Least Developed Countries (LDC) by 2026.

Last month I witnessed the changes in my daughter’s neighborhood as I took a daily three-block walk from her apartment building to a pristine one-mile walking park, lush with flowers and trees. The park is built around a small lake. A wide brick sidewalk encircles the lake and at one point crosses the water via a lovely bridge.

Hundreds of years ago, waterways flowed throughout Dhaka, but over the years, more land for construction was created by filling in narrow bodies of water with dirt, leaving isolated lakes instead of navigable waterways. Because the practice was illegal, vagrants did this work during the night. These are referred to as lakes but day-by-day, they shrink to ponds.

Aerial photo taken twenty years ago shows riverways closed into lakes by landfill.

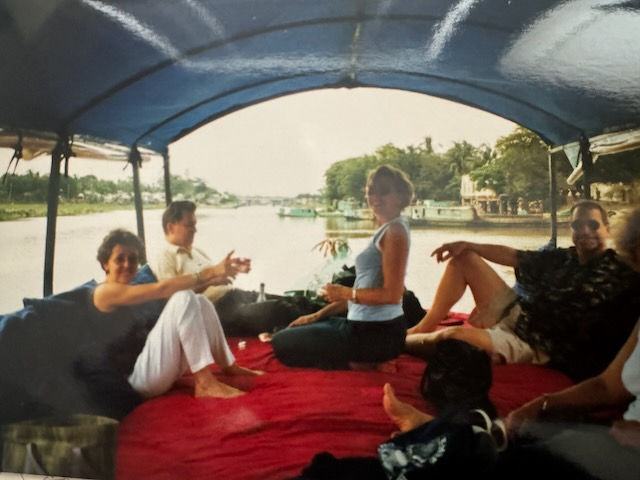

During our stay we enjoyed cocktails on our riverboat. These days it is impossible to find navigable waters close to our old neighborhood. That's me on the left.

Two of the “lakes” in Gulshan are now fenced parks, thankfully prohibiting further shrinkage or dumping. Our family had a coffee and stroll in the first one, Justice Shahabuddin Park our our first morning in Dhaka last month.

I remembered strolling with my friend, Rubina, around this lake twenty years ago as she bemoaned the litter, water pollution, and animal feces. Currently, she delights in her immaculate walking park.

Currently the park is manicured by a team of gardeners, paid for by the Gulshan Sociey. There’s a ladies’ corner, a badminton tournament court, and directional and health messages signage along the wide brick paths. Other features include a small amphitheater and a clean bathroom. There are guards at the gate controlling access. This was the second beautifully restored park I enjoyed on our visit back to the old neighborhoods in Dhaka. We had coffee and a stroll in the other Gulshan park with the kids on the first morning of our recent visit.

Along with the park, another striking difference in our daughter’s neighborhood compared to twenty years ago is that most street dogs in the diplomatic neighborhoods have been neutered and there are fewer of them. So, theoretically when this last batch lives out their life, street dogs in the diplomatic zone will become extinct.

But for now, it’s still cogent to mind your step and beware if passing by with an “outsider” dog. I noticed that when my daughter walks her two corgis (pictured on right, Shwari and Paxi), the street dogs may open one lazy eye and go back to sleep, or stand with open mouth waiting for a Milk Bone she tosses to them, a toll of sorts.

Her neighborhood street dogs reminded me of Tony, the black and white dog that patrolled our street twenty years ago when we lived in Dhaka. I was told that Tony once belonged to someone who lived in our neighborhood. They abandoned her to the street once they moved away. Perhaps she was rescued as a puppy, when their children begged to keep her; a temporary playmate not deemed worthy to export to wherever they were moving.

I didn’t understand why Tony, the street dog, growled viciously at me and not others. Well, I did give her a little kick one day when she tried to pounce on me. That might have something to do with it. Each day I walked out of our gate and looked for her. Once I spotted her, I would head out in the opposite direction, sometimes going out of my way to avoid Tony.

Photo: Our old street, Tony's block. In spite our her male name, Tony was a female and had several litters of puppies during our stay.

One night our family was coming home from dinner at a neighbor’s house. Suddenly Tony came up to us and started growling at me, teeth bared. I stepped back in fear. My daughter, who was home on college break, walked right up to the dog and swooped her under her arm in a tight grip with her hand forming a muzzle around Tony’s mouth. Bronwyn held her with force until we reached our house. The dog seemed paralyzed in terror. Finally, she put Tony down and the dog scampered away. Bronwyn instructed me: “You gotta show her who’s boss, Mom, or just bribe her.”

Not feeling very bossy, I decided on bribery. I started bringing bits of food in my pocket to toss to Tony. It only took a couple times before Tony started wagging her tail when she saw me, instead of growling. Such a wise daughter.

During our recent visit, I witnessed what lovely pets those street dogs want to be. Katerina, our daughter-by-heart, picked up two street dogs on March 8, several years ago. She named them Mira and Luna. Her mom, who was once a professional dog trainer, visits occasionally from Ukraine and has worked her magic on Mira and Luna. Here’s a short video clip of mom, Tamara, training the dogs.

In Bangladesh, mind your step. Besides sleeping dogs, the sidewalks require focus. The neighborhoods now have nicely bricked, sidewalks although they are constructed of different surfaces, patched together, making footing a bit unsteady. Once-gaping holes in sidewalks are now covered with grating. When I lived here a friend opened her car door and stepped into raw sewage up to her waist. Her husband pulled her out and walked her home to bathe in disinfectant.

The curbs are now elevated about one foot above the street and between the curb and street there is a concrete ditch intended to carry fast moving water during monsoon season when the skies empty torrents of water in the mornings and late afternoon.

To leave the sidewalk and cross the street requires an outstretched leg and trusty knees for a steady landing from the elevated curb to the street on the other side of the open drainage pipe. The upside to this challenge is that the design lessens the chances of walkers being swept away by seasonal monsoon rain.

Good exercise is provided on every block, as the walkways undulate, creating downspouts during the rainy season. So up and down and a bit sideways on the ankles as you walk by gates to apartment buildings. At these points, the sidewalk gives way to a sloping ramp, enabling cars to drive up the incline from street to the car park. So up and down and then sideways as I walk the street for morning exercise on my recent visit to Dhaka.

In the old days I had to look up as well as down. A tangle of illegal electrical wires and telephone connections hung like spider webs from street to buildings generally about ten feet above street level, but added wires and weight caused some to drop to head height. The wires are mostly tidy in the Gulshan area but not in Old Dhaka. So dunk down, walk sideways, and let sleeping dogs lie.

A few blocks from the diplomatic enclave, I cross a major intersection at my own peril. A two-lane street becomes four lanes of moving vehicles–cars, busses, motorcycles and small electric trucks in one direction and just across the median four more come from the opposite direction. In Bangladesh, traffic comes from the right. So look right first, then left, and back again. When we lived here from 2000-2005, I was thrown off guard by this chaos and cacophony, forcing me to discover a survival technique - embedding myself in a crowd of pedestrians and getting safely swooped across the street. These pedestrians are not cowards. They own the roads. Americans are a go-it-alone culture. Bangladeshis practice community.

The neighborhoods rumble with sounds of construction especially during the night when trucks are allowed to deliver concrete, sand and rebar rods. In years past, the wealthy neighborhoods of Gulshan and Baridara held only single-family houses. During our stay, the single-family homes were being replaced by seven-story apartment buildings. A developer would offer the owner two flats in the new seven-story building in exchange for their land. The previous owner would receive the penthouse as personal residence and another floor to sell. The developer profited from selling the other five.

While earthquake resilient standards were established twenty years ago, the engineers dramatically cut corners. When we lived in Dhaka and watched building construction, we realized that these seven-story buildings would quickly collapse in an earthquake.

The government now permits sixteen-story buildings with greater enforcement for building codes including earthquake resilience. The seven-story apartments built twenty years ago are now being demolished and rebuilt into super-modern steel and glass condo buildings. Besides stronger building codes, the buyers of these condos now demand proof that these standards were followed or employ their own engineers to watch the construction.

Twenty years ago we lived in a single family home at 21 Park Road on the corner of Road 5 in Baridara, a neighborhood next to Gulshan 1 and 2. Foreigners and wealthy Bangladeshis lived in these three neighborhoods. The three neighborhoods are referred to as The Diplomatic Zone. The American International School was located in Baridara, one street over from our house.

For the entire five years we lived there, an apartment building was under construction on the lot behind us. As it grew from sub-basement parking to four stories in height, the workers could look into the windows of our two-story house, but they showed little interest to do so. They had work to do hauling cement in buckets on their heads up and down ramps or tossing one brick to the next to the next like a fire brigade of old. We heard hammering, singing, yelling and bawdy laughter from a hundred workers wearing lungi cloths tied round their waste, the entire night every night for five years. We watched them more than they watched us, and plugged our ears to sleep.

Photos of our old neighborhood: Our white house from street view, the American Embassy and rickshaws lined up to take school kids home.

Below: two single family homes remain in Bronwyn's neighborhood.

A single-family home is now a relic of bygone days. From Bronwyn’s seventh story windows, we can see two private enclosed homes with gardens, surrounded by apartment buildings. These few remaining private homes are usually owned by foreign governments for Ambassadors or other senior staff. But overtime, these have become less popular with foreigners who prefer to live in a glistening glass tower with rooftop gardens, tennis courts and pools, versus a moldy cinderblock house.

Photo below: Apartment with tree top garden, seen from Bronwyn's window and to the right, Browny's glitzy apartment building where five ambassador's live. When she was assigned to this building, her dad remarked, "Security should be good."

In the old days the construction sites were draped in netting over the sides to catch falling bricks, providing more the appearance of safety measures than actual. Building machinery and techniques are now modernized. On this trip I noticed that the buildings are covered in heavy canvas, although the workers cut giant holes for air due to the intense heat inside. Construction engineers also build temporary structures along the sidewalks and over the streets with metal screening to catch any construction debris. Bronwyn says that using modern cranes and construction equipment, developers can now build a multi-storied building in one year. Bronwyn’s condo has triple-paned, sound-proof glass. During our visit, we could see the construction but could not hear it.

There are few beggars on the sidewalks these days. With the economy booming there are easier ways to make money than begging. When we lived in Bangladesh, a truck would deliver a chorus of singling legless beggars to the corner, a block away. During the day, they pushed themselves around the neighborhood on seat-size skateboards, singing while they held out a tin bowl. At five, a truck returned and took them away, receiving a cut of the beggar’s earnings.

Initially, I was one of those who looked alway from their deformity and crossed the street to avoid them. I was simply overhwelmed by the number of beggars on every corner. In contrast, my friend Kacie, whose house was by the drop-off point, got to know each one by name and their life stories, providing them with cool water when these sidewalks steamed from heat. When she told me this I felt shame. Kacie demonstrated that you don’t have to give money to a handicapped beggar but they do deserve kindness and respect.

When my niece Holly visited us for a month, she gave popsicles to a swarm of children sent out by their parents to beg in our neighborhood. Today these children are adults and their children are mostly in school.

On our recent morning walks, my husband and I witnessed a strange example of the changing modes of beggars and rickshaw traffic.

Not only do fewer beggars work the streets, but also, they use different ways of getting to the job. To our astonishment, we saw a woman driving an electric cart. She quickly turned the corner to chase us down. She pulled up beside us and the crippled man, perched on a bench in the back of the cart, descended and hobbled toward us with a cane and outstretched hand. Having no money on us, the ancient bearded man got back in the electric cart and his lady driver took off down the street searching for their next target.

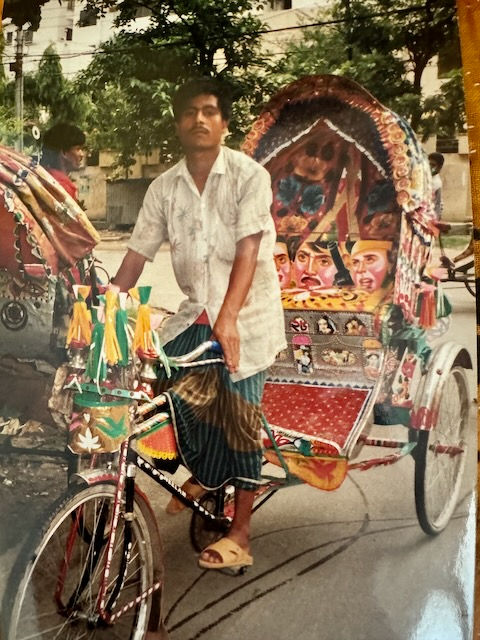

When we lived here, the area was choked with colorful rickshaws, ringing bells to attract patrons or alert walkers to get out of the way. Today rickshaws are restricted, with a designated number allowed in the area during established time periods.

I was sad to see that the colorful rickshaw paintings have been replaced by papered signs promoting health messages (above right). This appeared to be a misfired idea by some development group who thought it a grand idea but inadvertently killed an industry of rickshaw painters. Fortunately outlying towns are still awash in colorfully painted rickshaws and trucks, and electric vehicles abound. In these towns, rickshaw wallahs now buzz around easily, having turned peddle bikes into electric by attaching the pedals to small batteries. Such ingenuity has popped up all over the country except in the diplomatic neighborhoods where they are considered a hazard to the public who cannot hear them coming. The added danger of electric vehicles is the difficulty of stopping a fast moving rickshaw with a bicycle back pedal.

These days, a plethora of self-help guides encourage readers to be fully present in the moment. I got a head start in Bangladesh where street survival required paying close attention to my surroundings. I learned to see the world and myself through a different lens. So when I hear the phrase, “Let sleeping dogs lie,” I am reminded that Tony the street dog just craved a little kindness, as do we all.

In Bangladesh, mind your step and be present in the moment. Keep your eyes down for uneven sidewalks and look up to avoid hanging wires and falling bricks, greet legless beggars with a warm smile or frozen popsicle, watch out for electric bicycles and carts that move silently through the streets, and whenever possible let sleeping dogs lie.

Deborah's 3 Muses Blog

Written by Deborah Llewellyn, Beaufort, North Carolina

March 2024

Comments